Top 10 Tips for Working with Students Who Have Multiple Disabilities and Visual Impairments

Those of you who know me understand how passionate I am about children with Multiple AND Visual Disabilities. Here are my personal “Top 10 Tips” to guide in helping these special children grow and develop new skills for independence.

1. Believe in them!

Believe in the student‘s ability to learn something new– they can do it. This sounds easy, but it can be challenging when you have tried lots of things that haven’t worked. Hang in there and always remember that yes they can! My biggest initial failures often end up being my greatest successes in the long run.

2. Have a 4-year plan.

Start by developing long-term goals; what would the team like the student to be able to do in 4 years? Think functional and realistic, but don’t underestimate either. Use these long-term goals to guide the direction of the individual programs you develop and the annual goals. Give the student plenty of time to make progress because new skills usually are acquired slowly, it can take months to see even the smallest amount of progress. They will need all 4 years of regular work on these big skills to get where you want them to be.

3. Work together with team members.

Update other teachers, therapists and family members on progress and co-treat regularly with other members of the team. Working together regularly generates novel solutions to problems that pop up along the way. No one person has the answer alone; it is only by combining everyone’s skill sets and observations about the student’s progress that we have enough knowledge to create success. Finding ways to communicate with all of these people can be challenging – look for novel solutions to staying in regular contact. Use any and all means of keeping in touch with everyone else: group emails to talk about progress and ideas, phone/conference/Skype calls, home/school notebooks, home visits, plan your schedule to overlap with other therapists, be there at pick-up/drop-off times to have face time with parents, and schedule regular planning meeting that happen on a biweekly or monthly basis. I use all of these regularly to help me keep in contact with the multitude of people on my students’ teams.

4. Develop group goals.

Work together with others on the same goals so that students get lots of practice on the same things. TVI’s overlap particularly well with goals related to Literacy, Communication, Fine Motor Skills and Activities of Daily Living. COMS’ overlaps well with Gross Motor, Adaptive PE, Fine Motor, and Activities of Daily Living. Equally as important, work with families so that there is consistency between school and home.

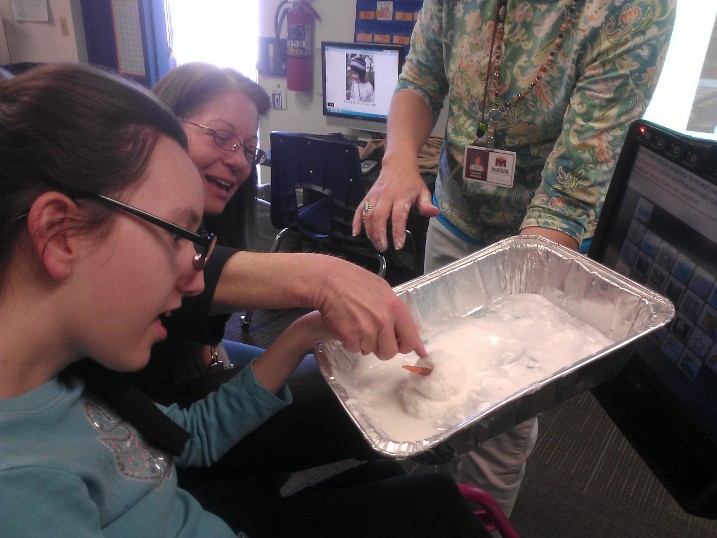

5. Work directly and often with the student and their paraprofessionals.

Work with the student at least 1-2 times a week, even if you aren’t the teacher on a day-to-day basis. Consultation on a monthly or bi-monthly basis is almost never effective. Model how to implement your strategies and activities with any Parapro’s that work with the student. Remember to check in with the Para’s regularly – they have the best feedback about how things are going, and often have the best ideas for solutions to problems that come up as well.

6. Wait for the student’s response.

Give plenty of wait time when looking for a student response – some students need 30+ seconds to even a full minute to assess the situation, figure out what they need to do, and then make their body do it. In addition, many students with multiple disabilities develop learned helplessness over time, knowing that if they just wait and do nothing someone else will do it for them. Don’t let yourself be the Magic Fairy! It’s OK to say things like “Hmm, I don’t know what urgh means, you might want to use your device so I understand you” – and then wait - even if you really know they probably want a snack.

7. Make decisions based on the type of communicator they are.

Work with the Speech & Language Therapist to determine what type of communicator the student is. Are they unintentional, intentional but informal, or a symbolic communicator? If the student is an unintentional communicator, focus on shaping how staff members respond to the student’s unintentional communications, including how we can shape a grunt or a point into a conversation. If they are intentional but informal, develop a plan to assist the student in becoming a symbolic communicator. If they are already using a symbolic means of communication, develop a plan to move the symbolic communication they are doing to the next level. For more information on how to help these students develop conversational skills, watch the webcast by Barbara Miles titled “Conversations: Connecting and Learning with Persons Who Are DeafBlind”

Work with the Speech & Language Therapist to determine what type of communicator the student is. Are they unintentional, intentional but informal, or a symbolic communicator? If the student is an unintentional communicator, focus on shaping how staff members respond to the student’s unintentional communications, including how we can shape a grunt or a point into a conversation. If they are intentional but informal, develop a plan to assist the student in becoming a symbolic communicator. If they are already using a symbolic means of communication, develop a plan to move the symbolic communication they are doing to the next level. For more information on how to help these students develop conversational skills, watch the webcast by Barbara Miles titled “Conversations: Connecting and Learning with Persons Who Are DeafBlind”

8. Make decisions based on their Learning Medium.

Use the student’s learning medium to drive decisions about what kind of abstract symbol system you will use with the student. The student’s Learning Medium is the primary way that they gather information - are they primarily using visual information, auditory information, or tactile information for learning? How they learn drives the type of Communicative Symbol System that will be most effective for the student. The TVI and the Speech & Language Therapist need to work together closely in determining the type of symbol system to use for communication. The way the student communicates will then drive decisions about a literacy system. This is a process that takes time and may involve several trials over a longer period of time before a final selection is made. For example, if the student is primarily an auditory learner but you select a visually based symbol system (such as Boardmaker Symbols), the student is not likely to be successful in mastering the visual symbols. You will end up thinking that they can’t learn to use a symbolic system when in actuality you are just using the wrong type of system. The process of selecting a symbol system can be complex, and remember that many students with CVI will be unable to use visually based 2-dimensional symbols. My greatest success recently is a student for whom we did it all wrong in multiple ways for about 2 years before we figured out how she CAN do it. For more information about this process, watch my webinar titled “Effective Access to Communication and Literacy for Students with Visual and Multiple Disabilities”.

9. Determine how the student will respond.

Work with other team members (usually SpEd Teacher, OT, and S&L) to determine how the student will indicate their response. Will they reach with their hand or another body part using a visually guided reach, search and select using tactile skills, use eye gaze, or choose an item from an auditory list by responding with a yes or no (with a sound or body movements)? This will be determined by combining their Preferred Learning Medium along with their functional vision and fine motor skills. Once the way the student responds best has been determined, make sure everyone who works with the student knows HOW they will respond. I create cards for staff to refer to that summarize this for each student and hang on their wheelchairs or have at their desks.

10. Trust your gut in regards to mastery.

Being data driven is important, but it can limit us as well. If you have mixed mastery data, go with your gut feeling about whether or not a student has mastered a skill. When you think they have mastered it, move on to teaching them the next steps. Often students with multiple disabilities aren’t able to show mastery of a skill at even an 80% level because of the multiple factors impacting their accuracy. It is tough to determine why these students make mistakes – are their mistakes because they don’t understand, because we haven’t made the skill or activity exciting or interesting for the student, because it is so hard to get their body to move in the way they want, because they are bored of working on the same thing for so long, or because they happened to be tired or sick that day? I often use 3/5 or even 2/3 trials as a mastery level rather than a higher 3/4 or 4/5 that we might expect for a student without motor issues. If you think the student “gets it”, then start teaching them the next skill on their path toward their long term goals. Students and teachers both get sick of over-working a specific skill for too long, and this really can limit progress in the long run. Conversely, when a student really doesn’t show mastery after a period of time, work with the team including para’s and parents to figure out WHY they haven’t really mastered the new skill. Use the WHY to help modify the approach so that it is successful.

Comments

I wish I could travel back in

time travel wishes

Personnel Prep and Trainings