Co-Creating Imaginative Stories

I’ve been helping kids tell their imaginative stories for almost twenty years. I once believed the myth that kids who have autism, and sometimes kids who have visual impairment or deafblindness, are not creative—that they are rigid and cannot move beyond a literal interpretation of the world. I’ve definitely given up this stereotype through my experience in helping kids share their play-based ideas with others in this project.

It began for me when I taught in an elementary support classroom for kids who had autism. These kids had normal vision and hearing, and shared many challenges in social learning, play and language with kids who have sensory impairments. Let me share some of the stories these kids co-created, which I later used with others who have sensory impairments.

Vegetable Vehicles

Ben was a first grader, and had a fascination with a book that had a picture of a “carrot car”. The book had a special picture of a car made from a carrot, with wheels made of slices of zucchini. Ben could hardly begin his day without carefully admiring the picture and placing it on a desk. The book was necessary for every transition, and he brought it with him to each class he attended throughout the school day. Teachers asked if we couldn’t “get past” the carrot car “obsession,” because they felt it interfered with his thinking. He asked me one day, "What would happen if there WAS a carrot car?” I decided this would be an interesting project for the play group that we had at lunch time, in which I was encouraging him to play with typical peers. I brought the topic up, and the group created a “plan book” of vegetable vehicles. Each child used their own medium (collage, drawing) to make a plan for a vegetable vehicle they would like to create. All of them had ideas, and Ben’s thinking didn’t seem so “strange” or “obsessive” to them! I bound the book, and brought in lots of vegetables and toothpicks. The group created a carrot car, a zucchini airplane, a broccoli bus, a banana boat, and string bean bicycles. I wish I could have captured Ben’s delight when the whole group propelled their vehicles down the hallways of the school to “block the bus lanes”—this activity was suggested by Ben, who heard a routine announcement every afternoon, regarding “A Ford Explorer is blocking the bus lane”. I found it interesting that his compulsive need for the Carrot Car book faded after this experience…it was as if he had been heard and his interest had been acknowledged.

Ben was a first grader, and had a fascination with a book that had a picture of a “carrot car”. The book had a special picture of a car made from a carrot, with wheels made of slices of zucchini. Ben could hardly begin his day without carefully admiring the picture and placing it on a desk. The book was necessary for every transition, and he brought it with him to each class he attended throughout the school day. Teachers asked if we couldn’t “get past” the carrot car “obsession,” because they felt it interfered with his thinking. He asked me one day, "What would happen if there WAS a carrot car?” I decided this would be an interesting project for the play group that we had at lunch time, in which I was encouraging him to play with typical peers. I brought the topic up, and the group created a “plan book” of vegetable vehicles. Each child used their own medium (collage, drawing) to make a plan for a vegetable vehicle they would like to create. All of them had ideas, and Ben’s thinking didn’t seem so “strange” or “obsessive” to them! I bound the book, and brought in lots of vegetables and toothpicks. The group created a carrot car, a zucchini airplane, a broccoli bus, a banana boat, and string bean bicycles. I wish I could have captured Ben’s delight when the whole group propelled their vehicles down the hallways of the school to “block the bus lanes”—this activity was suggested by Ben, who heard a routine announcement every afternoon, regarding “A Ford Explorer is blocking the bus lane”. I found it interesting that his compulsive need for the Carrot Car book faded after this experience…it was as if he had been heard and his interest had been acknowledged.

The Role of Writing in Supporting Play

Later that year, he became interested in an idea of building a “stretch limo.” One of my outstanding assistants showed up one morning with a large refrigerator box. The playgroup got to work and made a plan to build a stretch limo, adding a swimming pool and a garden in the back as Ben suggested. When it was completed, Ben got a gleam in his eye and said, “What would happen if we smashed it in the garage door?” Of course, we had to try it out, and the group went after school to Ben’s house, with the stretch limo packed in the back of a staff vehicle. We arrived at his house, and watched while the stretch limo was crushed by his garage door. Every one of the 5 kids was delighted, hopping up and down with joy!

Ben continued his interest in vehicles, and was employed later in life as a car detailer at an auto dealer.

My work with Ben got me thinking about the role of writing in supporting play with kids who have autism. I learned that tangible pictures can be used to share ideas. I learned to adjust my thoughts about kids with autism—they aren’t so rigid and “perseverative”—like other kids, they are creative and the stories in their heads can be appreciated and enacted with joy and delight.

Alphabet Book with Invented Words

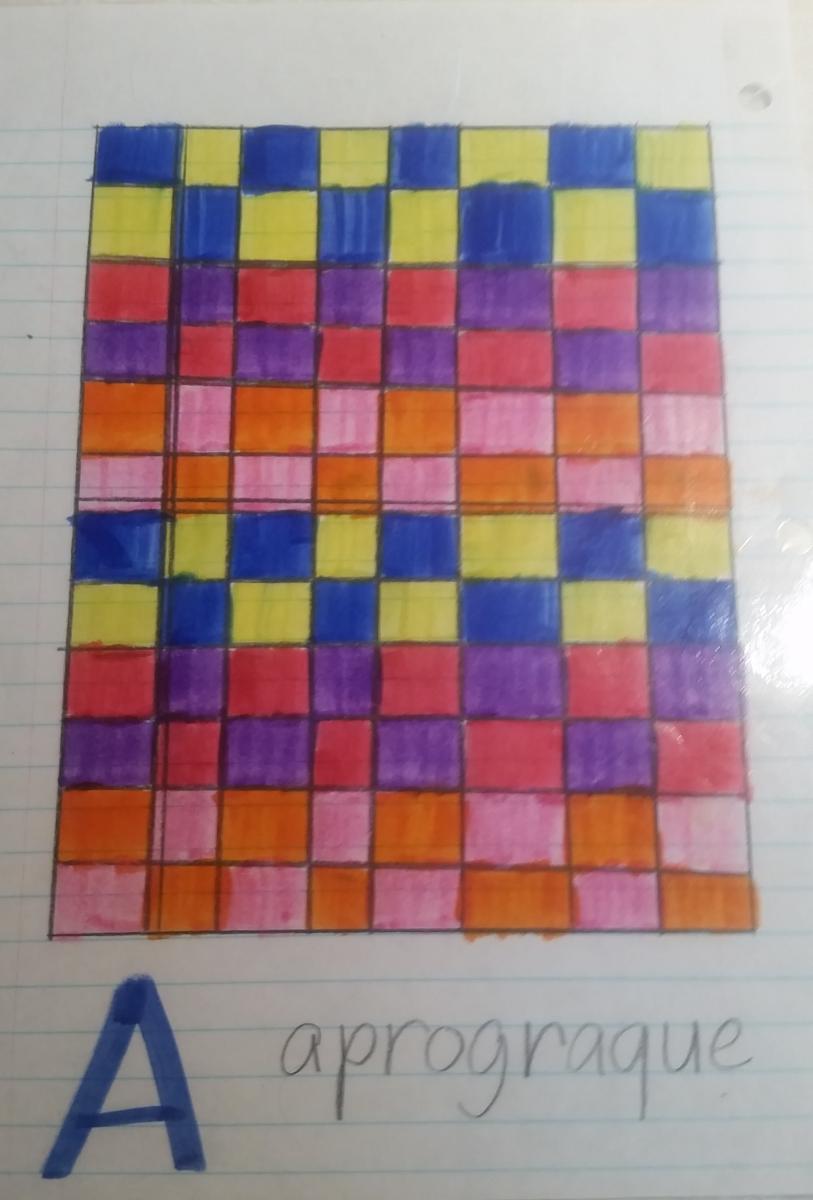

- A is for Aprograque (“a kind of a quilt”)

- K is for Kystrovelytor (“she wears them in her hair”)

- P is for Provatels (“the category that includes both birds and fish”)

- R is for Rascoltorsmatic (“the bottom part of the sled”)

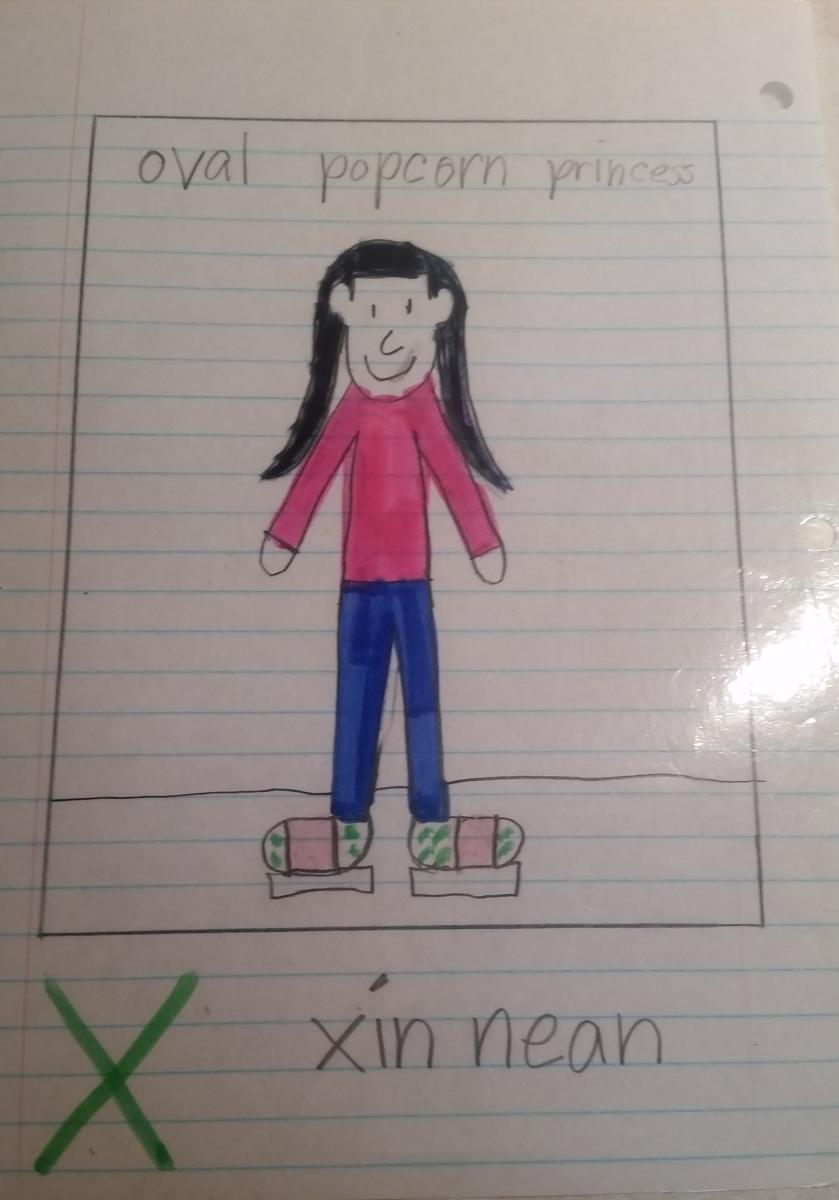

- X is for Xin Nean (“the oval popcorn princess”)

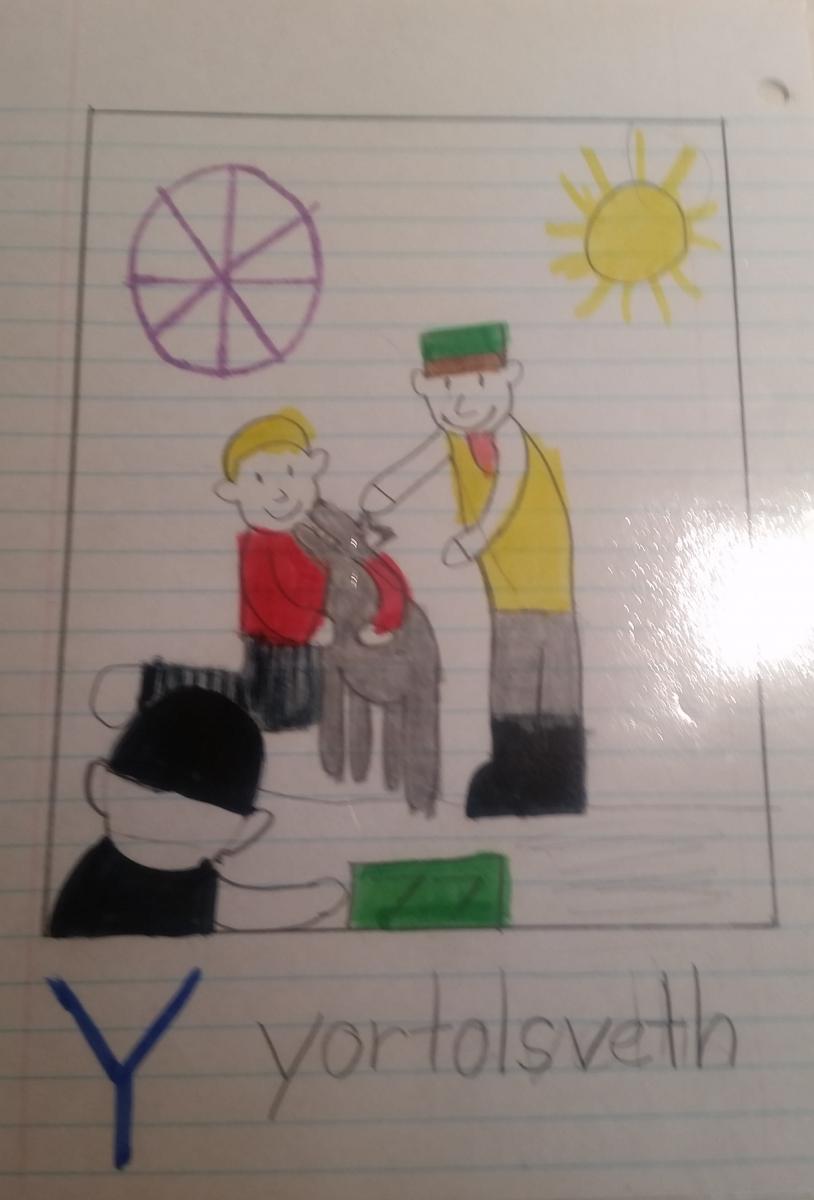

- Y is for Yortolsveth (‘he is the man with the camera, taking a picture of the boy and the dog")

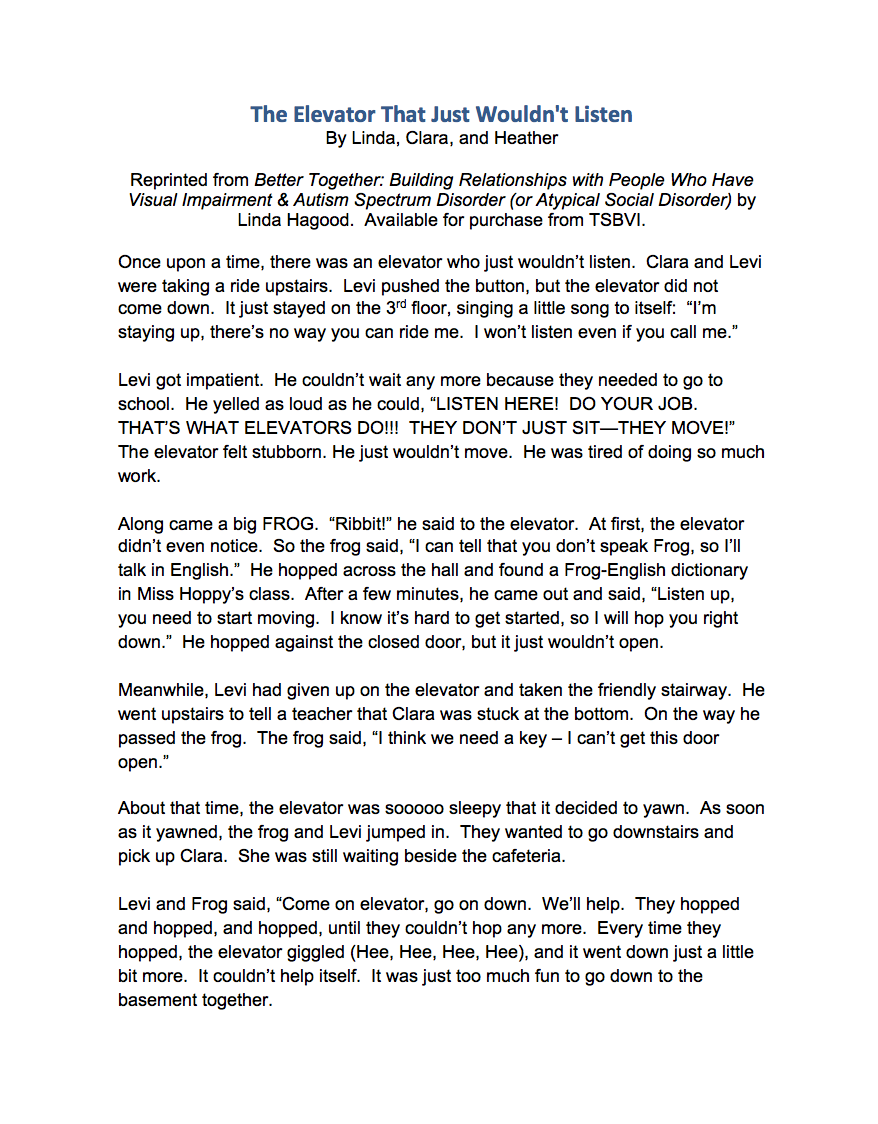

The Elevator That Just Wouldn't Listen

From Better Together: Building Relationships with People Who Have Visual Impairment & Autism Spectrum Disorder (or Atypical Social Disorder) by Linda Hagood. Available for purchase from TSBVI. Reprinted with permission.

- the elevator and the students' frustration with it

- the difficulties which Heather has in physical movement

- the students' need for support and camaraderie

Comments

Thanks!