Tactile Books for Very Young Children

Submitted by Holly Cooper on Apr 25, 2016

By Holly Cooper, Ph.D., Early Childhood Specialist, Texas Deafblind Project, Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired

By Holly Cooper, Ph.D., Early Childhood Specialist, Texas Deafblind Project, Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired - Approaches to Literacy Experiences for Infants

- When should braille be introduced in books?

- Adding tactile features to a book

- Creating an experience book

- Using real objects to accompany a book

It is amazing how early little humans show an interest in books! Typically developing children widely show an interest in children’s books by 12 months of age, and reading together with an infant is an enjoyable activity for the adult and child at age 9 months or even earlier. Experiences with books and literacy can vary widely in infancy. As with language and many other things, children from economically and educationally disadvantaged homes often have less access to books and literacy experiences. Children with disabilities are also at a disadvantage. Many of our children with visual impairment are born in very critical medical condition and remain so for a long period of time. They may be hospitalized or very fragile and have minimal opportunities to interact with people, toys, and books, or to have stories read to them. Children with severe and multiple disabilities are at a special disadvantage. Infants who are totally blind or functionally blind even without additional disabilities also have limited experiences with books, since most printed books are not meaningful and accessible to them.

Approaches to Literacy Experiences for Infants

There are two good approaches to offering literacy experiences to infants with blindness and visual impairment with additional disabilities: adapting books and creating books. Either approach to literacy must be based on a foundation of real experiences with real objects and people. Families, caregivers and educators must give children with disabilities a variety of experiences in the community and in nature to build a foundation of language and concepts for literacy. Children who are isolated indoors with limited opportunities to interact with others, especially other children, may not understand what many stories are about. Children who are isolated due to medical difficulties may still enjoy books with an entertaining language component, such as songs and finger plays, rhythmic language and rhymes. When I select books for very young babies, I look for books related to topics with which they have direct personal experience, such as body parts, feelings, routines of the day or activities of daily living. You can often find such books, or you can create them yourself.

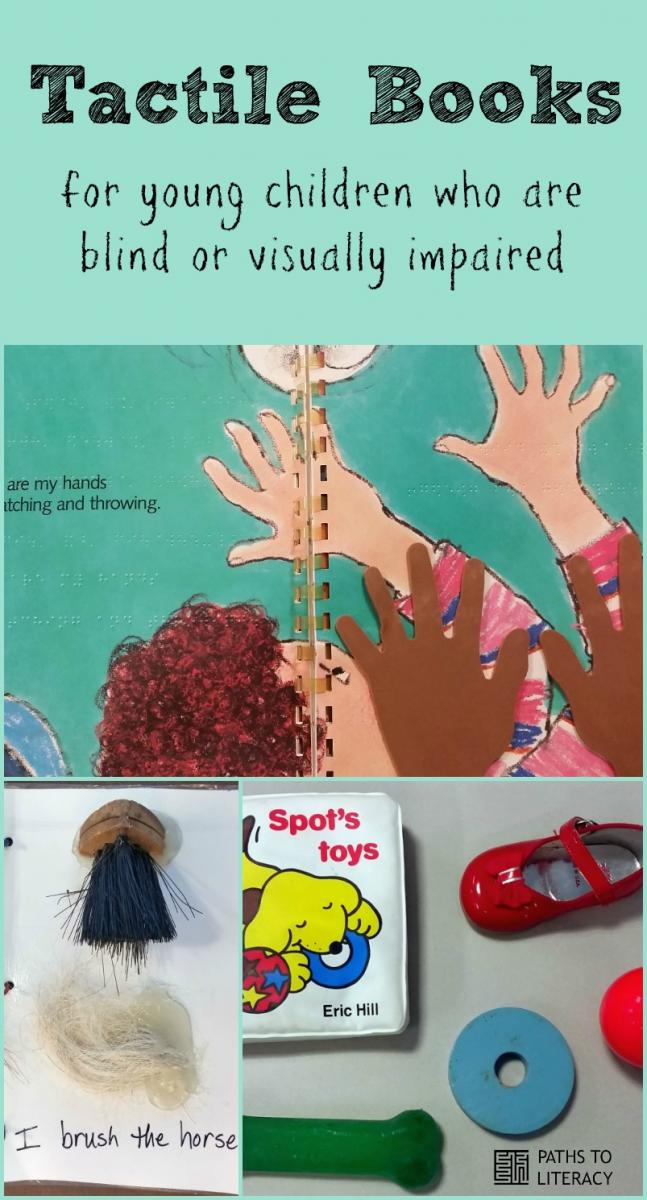

Here Are My Hands

by Bill Martin, Jr. and John Archambault

Henry Holt and Company, New York, NY (1985)

Softback: disassembled, laminated, brailled, and bound with comb binding

When should braille be introduced in books?

For a child who is blind or has a significant visual impairment, it is good to add braille to the book, or use a book with braille already in it. Even if the young child is not talking yet, having the text in braille helps build literacy awareness. When I’m reading to a child I also like to pretend to “read” the braille with my fingers, because that is the way the child will read, and reading tactually provides a good model for them to imitate. Braille can be added to almost any print book by brailling on adhesive braille products such as American Printing House for the Blind’s Braillables or in a pinch, clear contact paper. Braillable sheets can be inserted into an electronic or manual braille writer, or purchased in tractor feed sheets that can be used with a braille embosser. Then they can be trimmed and attached to the book’s pages. Clear contact paper is not as durable, and will not stick as long. Another alternative is to purchase a paperback book and cut the spine off and the pages apart and laminate it. The laminated pages can be brailled on, and the embossed dots are very durable. The book can then be re-assembled with a plastic comb binding or spiral binding. Unfortunately, most books for infants and toddlers are printed on heavy cardboard for durability, so can’t be put in a braille writer. For board books, Braillables are usually the best option. I also suggest using simple uncontracted or Grade 1 braille. This may be a suggestion some teachers disagree with, but I think simplifying the braille makes it more accessible to new readers because there are fewer characters and special rules.

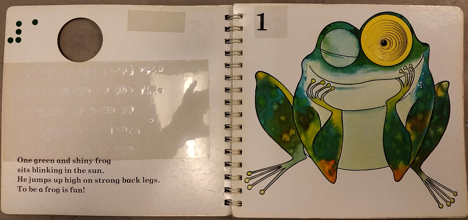

One Green Frog

La Coccinella Editrice, English text by Yvonne Hooker

Grosset and Dunlop, New York, NY (1981)

Board book with braille added using Braillables

Adding tactile features to a book

Tactile features can be added to a book, similar to some mass market children’s books such as Pat the Bunny. Some stories are easier than others to illustrate tactually. Look for stories with simple concrete references to objects with texture which you can add, such as blankets, washcloths, spoons, combs, and similar items. Avoid more abstract tactile illustrations such as rain, snow, ice, peanut butter, and other things which aren’t practical to add to a book.

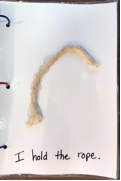

Creating an experience book

An alternative to finding a book and adapting it, is creating one especially for the child’s use. One beneficial approach is the use of “language experience books” or “experience books.” To create a book like this, an adult teams with the child and does an activity or participates in a special event with them. Perhaps it is going to the beach and swimming. The adult should explain to the child what will happen, then do the activity, then talk about it afterwards and write a short book about it. For a child who doesn’t yet have expressive language, using an activity that is repeated on a regular basis (such as going to bed) can help build language skills. For a child who is sighted, the adult and child can take photographs of the event, for a child who is blind or very young, small objects (sometimes referred to as “artifacts”) can be collected and glued in the book. Such a book might include something like this:

- We went on a trip in the car. I like to shake mommy’s keys when we go to the car. (glue a key to the page)

- We drove all the way to the beach. There was sand everywhere. (glue some sand or sand paper to the page)

- We went swimming in the water. It was cold! (some things don’t have an object to go with them)

- I liked to float on the noodle (or play with the beach ball, etc.) (Include a piece of noodle or ball)

- I got really tired. Mommy dried me off with a towel. (glue a piece of towel to the page)

- When we got home I fell fast asleep.

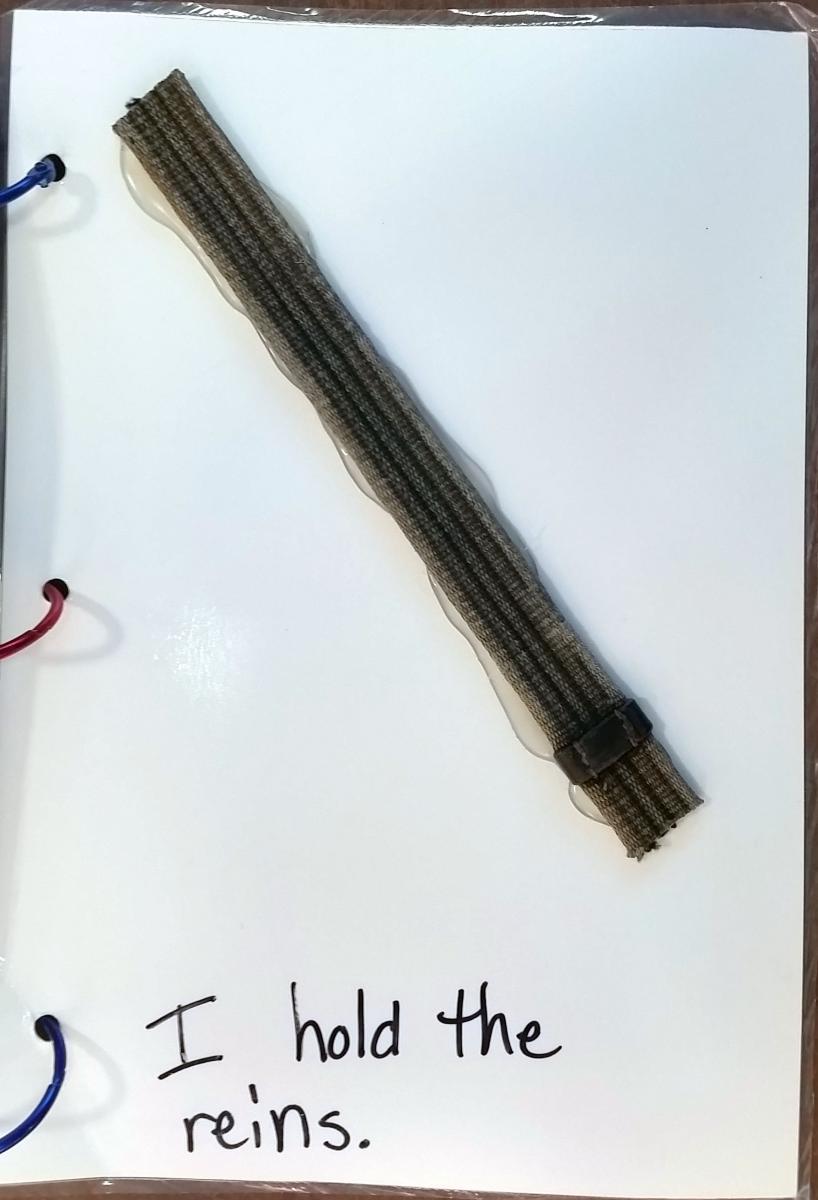

Below is a book from our library at Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired. It is about going horseback riding. The book’s creator went to considerable effort to collect real items to be included in this book.

Horses

By Carolina, former student at TSBVI

This book is part of a collection of object and tactile symbols books at the TSBVI library.

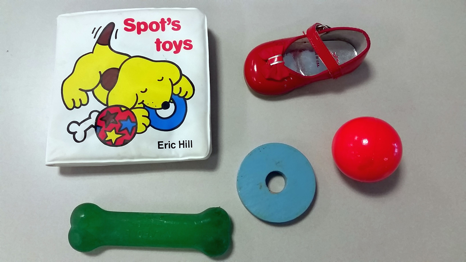

Using real objects to accompany a book

Clearly some experiences are easier to illustrate with tactile items glued to the page than others. Going to the rodeo might be more difficult. One farm animal feels much like another if you glue a fur sample to the page. Another way to make books is to use objects mentioned in the story, but not attach the objects to the book. If you make a trip to the farmer’s market, you can’t glue a tomato and a cucumber to the page, but you can read the story and explore real tomatoes and cucumbers together. It is also possible to find children’s books about simple familiar daily experiences and find objects to go with the story. It is important when doing this to use real objects as much as possible. Using a plastic cucumber and tomato for the farmer’s market story is not nearly as meaningful, since the weight, odor and texture of the vegetables is significantly different than toy food. Likewise, using miniature models such as toys is also usually not a good practice. Illustrating a trip to the rodeo with toy horses and cows does not give the child relevant information since toy horses bear little resemblance tactually to a real horse. In some cases, some creative license can be used, but it’s good to get some advice from your child’s teacher of students with visual impairment.

Spot's Toys

by Eric Hill

G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, NY (1984)

"bath tub book" edition with toys and objects

Building a foundation of life experiences

The most important part of literacy is to build a foundation of life experiences, talk or communicate with your child in their preferred communication mode (it might be sign language) about what you are doing together, and read stories together. Take time every day to read to your child. Reading specialists recommend reading aloud to children long after they have skills to read themselves, such as up to the middle school grades. Reading aloud gives them access to information they can’t read themselves and provides a skilled reading role model. Reading together also helps to build a special bond between yourself and your child supported by a shared experience of storytelling.

See Joseph's Bath Book: An Object Book for Early Literacy for an example of creating an object book about a familiar routine.

Resources

In addition to the resources on this site, some other good ideas for creating tactile experience books and adapting books include:

- Typhlo and Tactus book contest

- On the Way to Literacy

- Guide to Designing Tactile Illustrations for Children’s Books

Comments

Tactile Books

Supporting Literacy Skills