The Impact of Visual Fatigue for Students with Visual Impairment: Issues and Solutions

and by Marlena Chu, OD, FAAO

and by Marlena Chu, OD, FAAO

The visual demands of learning are constant as students progress through elementary, middle and high school. For students who have low vision, the impact of visual fatigue can challenge and impede educational progress. What are some of the causes of visual fatigue, how do you know if a student suffers from it, and what can be done to support student success when visual fatigue is a factor? Helping students with low vision who experience visual fatigue requires that caregivers and educators recognize the specific causes and symptoms. Identifying the cause will help students learn to skillfully utilize their individualized solutions, as well as advocate to others about their learning requirements.

Visual Fatigue and Learning

As children first learn to read, they must be able to maintain visual attention, fixate on and follow print comfortably as they are learning to decode letters, words and sentences. As reading and writing activities increase in complexity, more and more time is spent on a variety of tasks that require students to sustain those skills while applying cognitive skills. The goal of reading is comprehension, which is essential to learning. When a young child must expend extra energy on the physical task of reading, this effort can cause a decrease in comprehension and slow the learning process.

By the time students are in high school, they are required to use their visual skills to read text: in the distance on display boards, at near using textbooks, printed curricular materials, and on computers in the classroom and at home for completing homework. While most children build visual skills and stamina as their learning becomes more and more sophisticated, many students with low vision struggle to maintain academic parity with their peers because of issues related to low vision such as visual fatigue (Corn, Emerson, Jose, Bell, Wilcox, & Perez, 2001).

Causes of Visual Fatigue

Visual fatigue is common in the general population. It is typically attributed to inappropriate or inadequate spectacle prescriptions and/or inappropriate viewing behavior and conditions, including poor ergonomics and decreased visual hygiene. Visual hygiene can include eyestrain from decreased blink rate and prolonged accommodation.

Studies have shown that when reading or working on a computer, blink rate can decrease substantially, thus causing symptoms of eyestrain. Prolonged accommodation refers to sustained focus at a close distance, whether that is a reading distance or at a computer. Depending on the diagnosis, the low vision population may also encounter the following issues:

- Close viewing (which is common) demands more accommodation

- Difficulty maintaining monocular vision

- Decreased accommodation

- Glare sensitivity

- Decreased contrast sensitivity

- Central vision loss (including decreased visual acuities and central scotomas)

Central scotomas can also contribute to difficulty with tracking and crowding issues when reading.

Signs and Symptoms of Vision Fatigue

While each student with low vision is unique, there are certain symptoms of visual fatigue that are common. The following list of signs and symptoms of visual fatigue provides a helpful reference for educators and families supporting students with low vision:

- avoidance of visual activity

- blurred vision

- double vision

- headaches

- inability to change focus from near to far objects and vice versa

- increase in nystagmus

- loss of concentration

- sore eyes

- watering eyes

The student may experience fatigue 5-10 minutes after starting a vision-related activity. The differences in onset can vary with:

- cause of visual impairment

- the time of day

- intensity and type of visual activity

- previous exposure to the task, for instance knowledge of vocabulary and subject matter of the reading matter; whether the task is a test

- lighting and glare (Fitzmaurice, Gale & Lewis, 2004)

While a student may not experience all of these symptoms, it is important to identify and document any of these symptoms that may be present so that a remediation plan can be implemented.

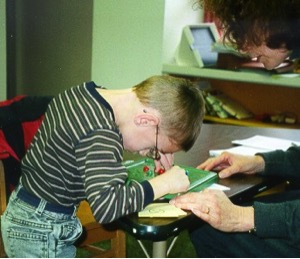

Physical and Postural Fatigue

In addition to eye strain, students with low vision are susceptible to physical and postural fatigue. When students are young, because some of them are able to accommodate, they may move closer to the print in order to increase the relative magnification, making it easier to see the print. Sometimes, they are as close as 1-2 inches from the print, bending over the desk or reading surface in cramped and uncomfortable positions. When this becomes a habit, they suffer from postural strain in addition to the visual fatigue. This may also lead to chronic neck and back pain.

Computer Use and Visual Fatigue

Computers are increasingly used as a curricular tool in school at every level. Children learn to use them on a daily basis beginning in elementary school and may experience many of the same symptoms related to computer use as adults. Extensive viewing of the computer screen can lead to eye discomfort, fatigue, blurred vision and headaches, dry eyes and other symptoms of eyestrain (Kozeis, 2009).

Students with low vision benefit from the accessibility features of computers that allow them to personalize their own modifications to print size, spacing and contrast, as well as pairing print with auditory features. This is very advantageous, but it means that sometimes students with low vision are using the computer even more than their classmates, putting them at risk for an additional source of visual fatigue.

Solutions

Assessment and collaboration

Depending on the causes and symptoms of visual fatigue, there are many ways to lessen and reduce it, ensuring that students with low vision learn at their highest ability with comfort. This begins by becoming knowledgeable about the cause of visual impairment from medical documentation and through regular visits to the vision specialist. Ideally, a student should have a low vision exam by an optometrist who specializes in assessment of a person’s functional vision capabilities, needs and limitations. The low vision specialist should be able to prescribe optical and non-optical tools that will help maximize use of vision. It is optimal for the Teacher of Students with Visual Impairment (TVI) to attend the low vision exam with their students, so that she/he can provide observational input to the process and gain first-hand knowledge about student visual functioning from the low vision specialist’s perspective.

Observation of the student in the classroom by the TVI during all aspects of learning will provide first-hand information of symptoms of visual fatigue, using checklists to provide documentation that will serve as justification for support and modifications during the IEP process. Included in the observational report should be information about supports in the learning environment that are beneficial to the student.

Ensuring appropriate prescription

Many students benefit from prescribed corrective glasses for reading and/or distance. When this is the case, it is important to regularly check in with the eye care specialist to ensure that the prescription is appropriate or can be fine-tuned as needed.

Use of appropriate low vision aids

Low vision aids can substantially decrease visual fatigue. Devices that can increase print size and contrast enable a student to read longer without visual strain, using more ergonomically correct posture, therefore reducing an additional cause of fatigue while reading. Use of low vision aids, such as magnifiers, monoculars, and electronic magnification systems can be assessed and prescribed by a low vision specialist who will determine the most beneficial level of magnification to meet specific individual needs.

When low vision devices are prescribed, it is often necessary to provide instruction and practice with them until the student becomes comfortable using them regularly throughout the day. Because low vision devices are unique to students with low vision, they may be reluctant to use them in the classroom because they resist appearing different than their peers. When this is the case, it’s even more important for the TVI to provide regular opportunities to practice using the devices with the students’ curricular materials, so that they begin to appreciate the benefit of the devices.

It’s helpful for the TVI and classroom teacher to collaborate about opportunities for students to regularly use their low vision devices. For young children, it’s sometimes helpful to set up a chart that includes regular activities throughout the day and to determine with the student which device would be most helpful to successfully complete the activity. Each time the student uses a device appropriately for an activity, a sticker or mark can be made on the chart. At the end of the pre-set time, the student can be rewarded for using the devices. The goal is to help the student get into the habit of using low vision devices at an early age, so that the habit is in place as needs increase with curricular challenges.

Lighting

Many types of visual impairment include decreased contrast sensitivity or, the ability to determine objects/symbols in contrast to the background. This is a skill that is essential for reading, seeing detail and for safe mobility. When a student experiences decreased contrast, they may strain their vision in order to read in dim or even normal lighting situations. Add to this the tendency for students with low vision to bend over their reading material in order to get close enough to read it, casting a shadow on the text, which makes it even more challenging for them to make out print that may not be of high contrast.

Providing the right type of lighting is essential. Ensure that each environment in which the student is reading and writing is well-lit to begin with, and provide task lighting that can be directed on reading and writing surfaces. A light that can be positioned to cast a wide swath of light on the reading/writing area by bending, and lighting settings that can be fine-tuned in terms of both dimming and spectrum are optimal.

Postural Support

Because many students with low vision bend their heads, necks and backs forward in order to more clearly see and read curricular materials, they are susceptible to postural strain and fatigue, as well as visual fatigue. Because it’s difficult to remain bent forward for a long period of time, this lessens the time that students are willing to read and work continuously on school assignments.

Building good habits of ergonomics from an early age is important, including making sure that furniture is well fitted to the student at each age, so that they are able to sit comfortably with feet on the floor and viewing print at eye level. Book and writing stands can be used to elevate reading and writing materials to lessen bending over learning materials.

Good posture is also important when using the computer. The monitor and keyboard should be positioned according to the size of the student, with feet on the floor, hands resting comfortably on the keyboard with elbows bent, and the screen positioned so that it is easily viewed with chin, neck and head in a natural position, rather than straining to look up or hunch forward. An adjustable chair can be helpful.

Computer Practices

As mentioned previously, the benefits of computer use for students with low vision are many and so it’s important that students employ practices that will decrease visual fatigue. This begins with adjusting the computer accessibility settings to meet the student’s learning requirements, including text font and size, contrast, cursor and pointer size, screen magnification and use of a screen reader. These modifications can be easily made in most computer systems.

Carefully check for glare on the computer screen caused by light sources, such as windows and doors, and turn the screen in a different direction to eliminate the glare. Reducing the general room lighting, when possible, will increase the contrast on the screen, making it easier to read.

Scheduling rest periods when using a computer is very important. Some guidelines suggest the 20/20/20 rule – every 20 minutes, take a 20-second break, and look 20 feet away. This will relax accommodation and encourage blinking, refreshing the tear layer and hopefully decrease or prevent symptoms of eye strain. Others recommend a ten-minute break for every hour of work. The break should include walking away from the computer and enjoying something that does not use near vision. Some students will require shorter duration on the computer; it is important to carefully assess the individual needs of each student.

Building Auditory Skills

One essential way to lighten the visual load and lessen visual fatigue is through listening to curricular materials, rather than reading. Students are able to access most classroom textbooks and recreational reading material through listening to either live recordings or digital textbooks. This is a skill that should be developed in tandem with other literacy skill development, beginning when children are young by making available books to listen to for enjoyment through the Talking Books Program. Gradually, as students progress in late elementary through high school, they can learn listen to non-fiction and textbooks as the curricular requirements increase. Learning to listen to chapters in social studies and science in tandem with print assignments, for instance, is a skill that can greatly decrease a student’s visual fatigue and provide access to curricular materials that may be otherwise avoided.

Accommodations

In order to ensure that students with low vision have appropriate accommodations in place to address visual fatigue, it is important to articulate various aspects of their learning environment through the IEP process. The following examples of recommendations may be appropriate:

Testing

- This student requires additional testing time (two times).

- Provide alternate options to marking Scantron (bubble marks), such as marking in the test booklet or providing a scribe.

Lighting

- This student will benefit from additional task lighting during near tasks, such as reading or writing at a desk.

Glare

- When possible, keep blinds closed during the sunniest times of the day.

- Make sure that learning surfaces (such as computer screens, white boards, desks) are glare free, by closing blinds or turning surfaces away from glare-producing areas.

- If necessary and helpful, allow ____________to wear a hat with a brim in bright classrooms.

- Outside: __________ should wear a hat with a brim in addition to sunglasses.

Self-Advocacy

Helping students with low vision who experience visual fatigue includes teaching them skills of self-advocacy. When children are in early elementary school, it is appropriate to begin teaching them about their visual impairment and about their individual learning requirements. As they mature, the detail and language will increase, as will expectations that they will be able to self-advocate to others in a manner that is clear and polite, yet assertive.

Helping students with low vision who experience visual fatigue requires that caregivers and educators recognize the specific causes and symptoms, so that they can help students learn to skillfully utilize their individualized solutions, as well as advocate to others about their learning requirements.

References

Corn, A.L., Emerson, R.S.W.,Jose, R.T., Bell, J.K., Wilcox, K. & Perez, A., (2001). An initial study of reading and comprehension rates for students who received optical devices. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, December.

Fitzmaurice, K., Gale, G., & Lewis, D. (2004). Statewide Vision Resource Center, Retrieved June/25/19 from http://svrc.vic.edu.au

Kozeis N., (2009) Impact of computer use on children’s vision. Hippokratia. Oct-Dec; 13(4): 230-231.

With gratitude to Ian Bailey, Emeritus Professor of Optometry and Vision Science, University of California, Berkeley