Walking Through Stories: A Literacy Strategy for Reading to Young Children and Early Readers

Once upon a time, there lived a spleeth. This spleeth was the lipliest spleeth in all the land. One morning, the spleeth decided that he needed to haynder to see if he could get some rukyas. Sadly, the plupet did not have any rukyas, so the spleeth knew that he was trased. Walking home, the spleeth heard a rukya! The day was saved! The spleeth and his family could have breakfast.

Do you know what a spleeth is? How about a rukya? Before the last sentence, did you think it was something to eat? What does it mean to haynder or to be trased? Does your town have a plupet? If the story had pictures of a spleeth and rukya, would that have helped you understand more quickly?

Understanding Concepts is Key!

When reading, understanding is key; it is not enough to hear or read the words. Those words need to have meaning, and that meaning is dependent on our experiences and understanding of concepts. If I have never heard of a bear and had never seen a picture of one, would Goldilocks and the Three Bears have the same meaning?

For children with vision, a common strategy that familiarizes students with a text prior to reading is to take a Picture Walk. Children and students preview images to activate prior or background knowledge and to enhance comprehension (Learn Alberta, 2019). Students are able to make sense of unfamiliar vocabulary and concepts prior to engaging with the text and can therefore gain greater meaning from the story, because they can connect the visual images to their own experiences (Milne, 2014). Taking a picture walk also helps students anticipate what they will read (Vanderbilt University, 2019). As they explore a book’s front and back covers, images, and learn the title, students can use what they have gathered from the book to make predictions.

But what do we do for a child who cannot see the pictures well, or at all? How can we develop concepts and activate their background knowledge and experiences? For students with a vision impairment, this process of taking a “picture walk” with a new text is just as, if not more important in order for them to gain understanding and make connections with the text. We need to move beyond the illustrations and help students recall concrete experiences, or provide some if needed.

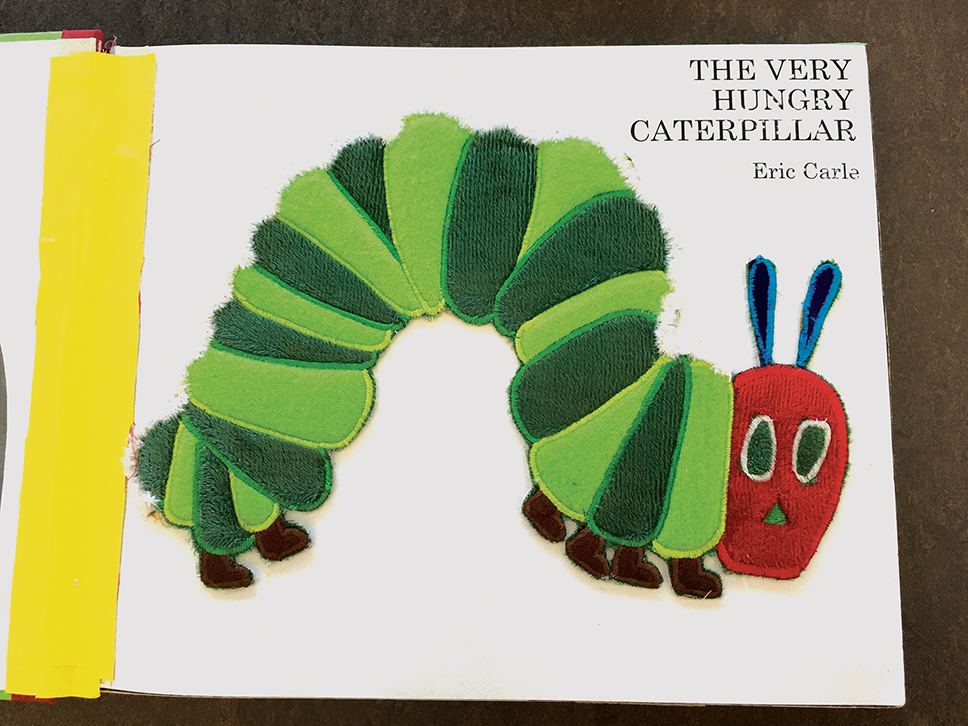

To illustrate the process of taking a book or picture walk with a child who is blind or visually impaired, we will refer to the popular book, The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle. This is a fantastic story that is available in various media (i.e. braille, tactile, YouTube, etc.) and is certainly one of my favorites.

Step1: Explore the Title

The first part of any story or book is the title. This is a great opportunity to stir your child’s interest in what you are about to read. Asking, “What do you think this book will be about?” will help to build prediction skills.

Examples:

- “Our story today is The Very Hungry Caterpillar. Have you ever held a caterpillar? What do you know about caterpillars?”

- “Remember that time we found the caterpillar in the garden? What did it feel like?” (Or even better, “Here is a caterpillar. Let’s let it crawl on your hand.”)

- “This caterpillar eats and eats! What do you think will happen as he keeps eating? What kinds of things do you think he eats?”

Step 2: Picture/Book Walk

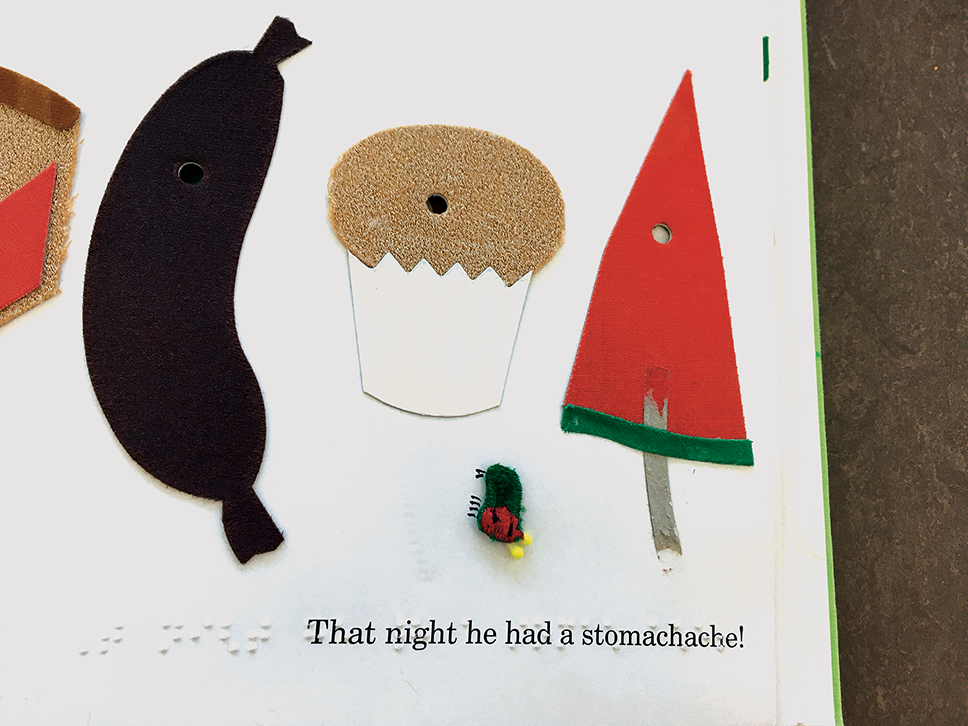

Slowly flip the pages of the book and explore some of the pictures. You can go page by page, or for longer books, choose a handful of pictures in advance. For children with some vision, ask questions about what they see. “What is going on here?” “Who is this?” “Why do you think they are there?” For children without vision, describe the picture and ask similar questions. Use this time to make sure your child understands key vocabulary they will encounter in the story. For The Very Hungry Caterpillar, some of the important vocabulary words might include:

- the days of the week

- fruit names such as plum, pear, apple

- egg

- leaf

- cocoon

It will be important to have as many real examples of the core words as possible to build your child’s concept development. For this story, letting your child touch, explore, and taste the different fruit the caterpillar eats will give them concrete experiences and enhance their understanding of the story.

Examples:

- “On this page, there is a picture of a big, red apple. What do you think the caterpillar does with the apple? Do you like apples? What do they taste like?”

- “This page has a picture of two pears. Here is a pear. Tell me what it feels like. Let’s see what it tastes like.”

- “Here the caterpillar has a stomachache. Why do you think he is going to get one?”

Remember, don’t give away the story! Let your responses to your child be vague. “That’s very possible!” and “We’ll have to read and find out!” are some good phrases to encourage dialogue without giving away too much of the story.

Step 3: Read the Story

Now it’s time to read the story! Use some of the same questioning strategies as you read. Refer back to statements your child made as they predicted what might happen in the story. This is very beneficial because it reinforces critical thinking skills that you activated during the picture walk. As with the picture walk, build in moments of interacting with real objects as much as possible. Make sure to ask open-ended questions instead of yes/no questions, and ask questions that both require fact recall (who, where, what) and inference (why, how). Guide your child to think of memories that remind them of characters or events in the story. These connections help build their concept development and can make reading experiences more dynamic.

Examples:

- After reading what the caterpillar eats on Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, pause and ask, “What do you think he is going to eat on Thursday? How many will he eat?”

- “Remember after Thanksgiving when everyone’s tummies felt so full? I bet that’s how the caterpillar feels!”

- When he builds the cocoon around himself ask, “What do you think will happen when he comes out?”

Finally, when you come to the end of the story, “walk backwards” with your child. Ask them if their predictions were correct. Discuss any surprises in the plot and ask why they think the story ended that way. Take a few minutes to review the new words and concepts that you reviewed before reading. If necessary, eat more fruit!

Using this strategy of “walking” through a story is a great way to pique a child’s interest and improve their comprehension of the story. Providing them with descriptions and concrete examples of what is in the pictures and then asking them questions helps to stir their imagination while building their concept development. Remember, literacy is much more than being able to read words on a page…it is about building understanding and providing experiences with those words.

References

Learn Alberta. (2019). "Picture Walk". Retrieved from Strategies that make a difference: http://www.learnalberta.ca/content/ieptlibrary/documents/en/is/picture_walk.pdf

Milne, E. (2014). "Taking a Picture Walk". Retrieved from Hands and Voices: https://www.handsandvoices.org/articles/education/ed/V11-2_picturewalk.htm

Vanderbilt University. (2019). "Taking a Book Walk". Retrieved from Iris Center: https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/rti03/cresource/q3/p08/

Reprinted with permission from TX SenseAbilities.