Using Printed Words with Students with CVI, Phase III

This week I arrived at a school just as Justine, a beautiful little four-year-old girl, arrived off her bus. Justine was recently diagnosed with cortical visual impairment (CVI) and is in Phase III on the CVI Range (Roman-Lantzy). She has some gross motor challenges, is verbal, but has limited expressive language. Like many children who have CVI, Justine has seizures.

This week I arrived at a school just as Justine, a beautiful little four-year-old girl, arrived off her bus. Justine was recently diagnosed with cortical visual impairment (CVI) and is in Phase III on the CVI Range (Roman-Lantzy). She has some gross motor challenges, is verbal, but has limited expressive language. Like many children who have CVI, Justine has seizures.

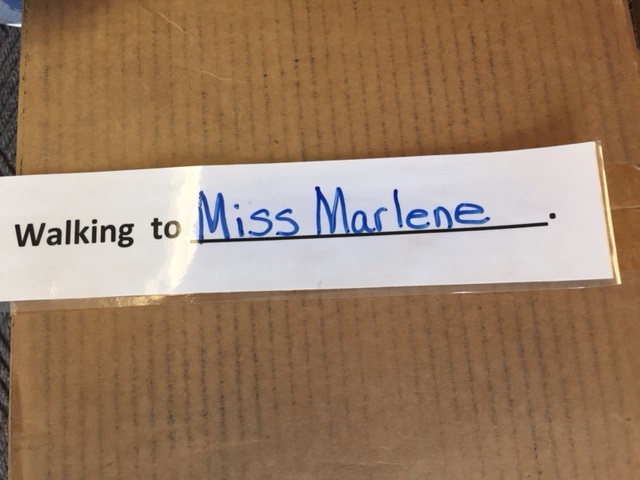

On this morning, Justine’s paraprofessional greeted her very differently. She handed Justine a card with the words “Walking to Miss Marlene ” written on it. The para told her, “We are walking to Miss Marlene!” She gave Justine time to look at the card (visual latency), and then, carrying the word card, Justine walked straight to Miss Marlene’s physical therapy (PT) room.

This was a dramatically different beginning to school than any previous day. Justine’s reaction was different too. Usually, Justine is ushered into the chaotic hallway scene (complexity of array, distance, movement, sensory complexity, visual fields) amongst a rush of students and teachers, busy visual displays on the walls and conversation. From there, she is escorted down the hallway with other friends to her classroom (complexity, light, movement, visual fields). Walking directly to PT upon arrival could have easily caused Justine to have a CVI meltdown because it is different from her morning routine of getting off the bus and walking straight to class (challenges with complexity, novelty).

How was it that showing her these four written words on a card produced such a different reaction?

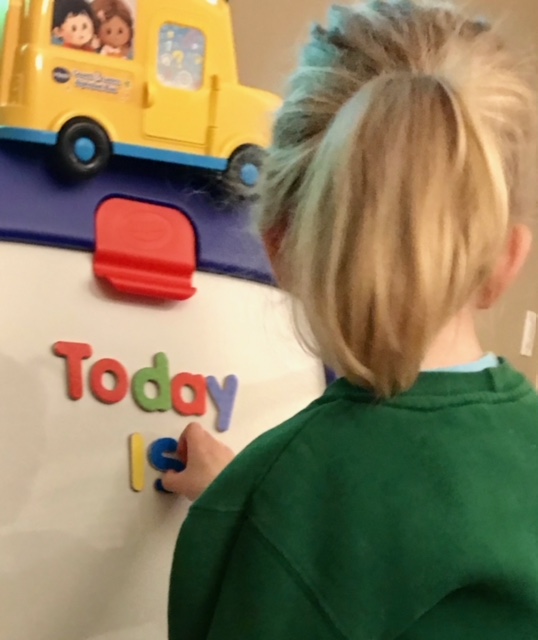

Over the past year, we have noticed that Justine loves letters and words. We suspected she may be reading but due to her inconsistent visual and verbal responses, we could not be sure. At only four years old, we did not want to force reading on Justine, or insist that she show us what she knew, or build a program around words when we were uncertain of her skill level.

Recently, however, we noticed her response to printed out word cards on a table in her classroom that had been set out for another student. On her own, Justine went over to the table, looked at the cards, read some out loud, sounded some out, sorted through them, and seemed to greatly enjoy the experience. Seeing this, her team decided to try something a bit radical: use Justine’s love of “literacy” to help her be more organized and focused. They printed out cards for her to use throughout the school day. One card reads:

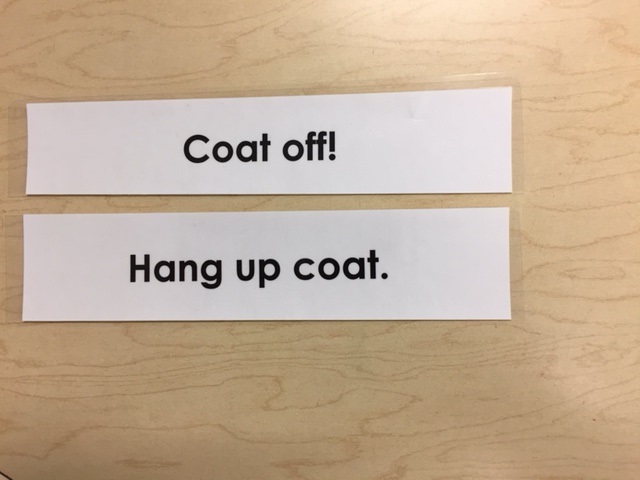

Coat off!

Hang up coat.

Put away lunchbox.

At the start of every school day, Justine is always asked to do these three things, in that order. Many times, though, she is unable to comply. There is so much going on in the classroom when this is expected of her, and she is just making the transition to school, sometimes even sleeping on the bus when she arrives (complexity).

After her PT session, upon arriving in her classroom, Justine is asked to do these three things. The corresponding cards are held up, she is given time to look and read (visual latency). After she has some time with the words, she immediately completes what is being asked of her.

How is the written word, or her newfound literacy, helping Justine?

For children in Phase III CVI, we are learning that sometimes letters and words are more “stable”than pictures. That is, the shape and look of a word, despite being more abstract, are more consistent than pictures. (Roman)

Think about a cat: there are thousands of ways we can depict a cat in a picture. But the word “cat” looks similar no matter how it is written. This stability can be helpful to a child with CVI.

With this in mind, we can further understand how this strategy helps Justine by considering her auditory processing. With all the noise and chaos of a typical preschool environment, Justine’s comprehension and focus become quite compromised. During busy and noisy times in her school day, she sometimes breaks down into tears. When she has the chance to see sight words, it seems to boost or support the auditory input. This enables her to be much more focused and she is then able to process the information.

Perhaps the sight words help her filter out the noise and busyness that surround her.

Justine has difficulties recognizing friends by their faces. We have instituted ways to help her know who is near her and who she is playing with, by naming a child (“Alex is sitting next to you!”) and by using descriptive language (“ Alex is wearing his blue T-shirt today”) to help her across her day at school. This could be ventral stream dysfunction, with ventral stream associated with recognizing faces. It could also be dorsal stream difficulty: being able to discern who somebody or what something is when it moves or is moving. Our brains stabilize these images for us. Her peers are four years old and constantly on the move!

Now that we see her ability to read words so easily and quickly, we can have each child in her classroom wear a name tag, so she will be no longer be as dependent upon adults to help her know who her peers are.

Finally, when we utilize Justine’s strengths and passions (letters/words), we meet her where she is. She responds in kind by thoroughly enjoying the input and capitalizing on it. Aren’t we all more likely to respond more quickly, and be successful with topics that interest us?

*Peggy Palmer, M.A. Peg is a Teacher of the Visually Impaired (TVI) working at Bureau of Education and Services for the Blind (BESB) in Connecticut for over 20 years, specializing in young children, ages birth to five. Peg is a Perkins-Roman CVI Endorsee.

This post was originally published on Start Seeing CVI