Tips on Using a CVI Overlay in a Child’s School Day

While the specifics mentioned below were developed to meet the needs of my grandson in conjunction with his CVI Range assessment (Roman-Lantzy), this approach may be helpful to others as you map out the accommodations necessary to address the CVI characteristics of your student or child. My grandson, who is in 4th grade, is in Phase III on the CVI Range and the ideas presented here represent an application of what I have learned from Dr. Christine-Roman Lantzy, Matt Tietjen, and others. I recently presented a webinar for Perkins eLearning called "Our CVI Literacy Journey into Phase III". Watch the webinar to learn more.

General Tips

- Educate yourself about CVI (cortical visual impairment) by reading Dr. Christine Roman-Lantzy’s Cortical Visual Impairment: An Approach to Assessment and Intervention.

- Watch webinars and read information online, through reputable authoritative sites.

- Attend conferences and workshops, or participate in online training.

- Connect all objects, experiences and words to the child.

- Ask, “What do you see?” to better understand his or her visual world.

- Remember that what those of us with typical vision see is not the child’s visual reality.

- Always keep in mind that looking and seeing is NOT the same as being able to interpret visual information.

- Be aware that lack of eye contact does not mean that the child is not listening.

- Let the student know the goal of each task or activity.

What Is a CVI Overlay?

The CVI Overlay refers to the impact of the 10 CVI Characteristics on a child's visual functioning. It is important to begin this process with a CVI Range assessment with a qualified professional, who is familiar with the Range and its implications. CVI overlay is centered on the child’s CVI characteristics and as those characteristics change, the modifications and supports will change.

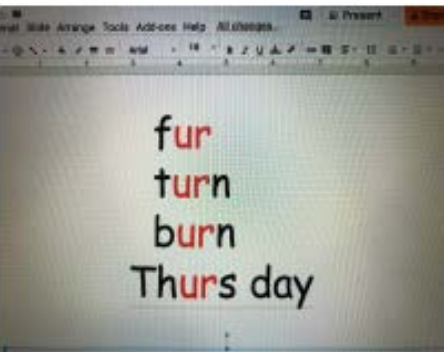

Color Preference

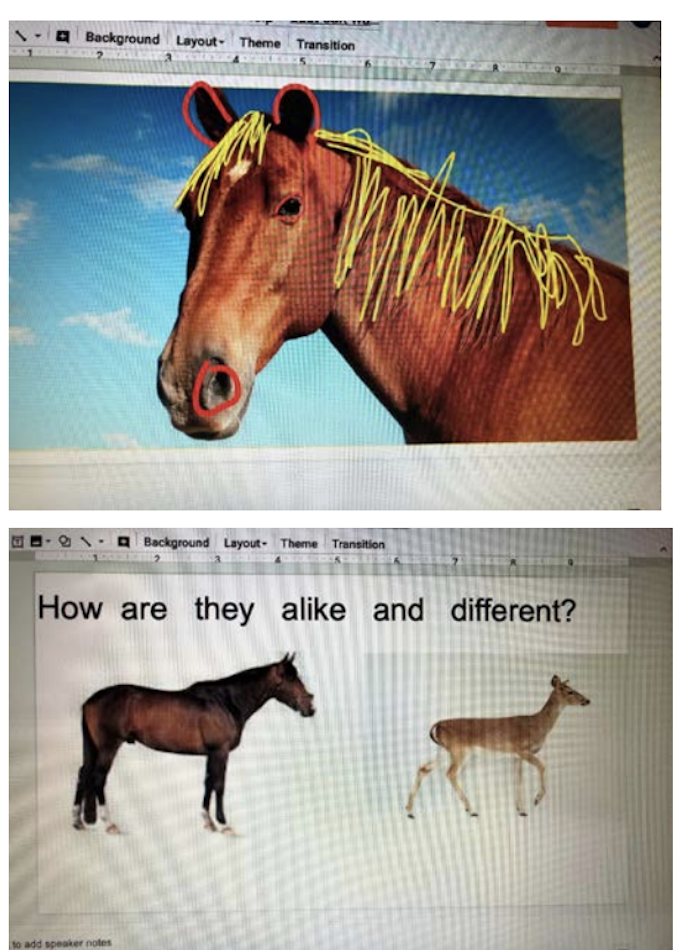

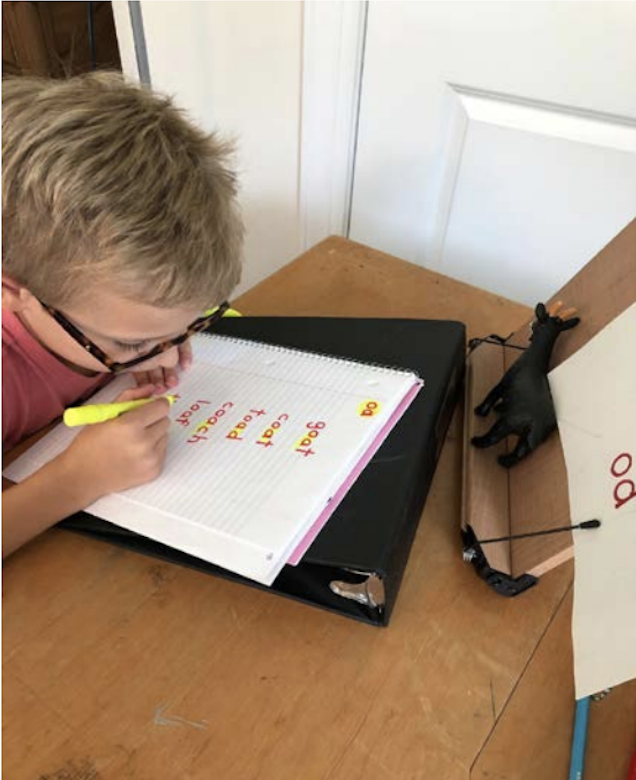

Once you have identified the child’s preferred colors, use them as a visual support and to draw attention. In the photos below, my grandson River’s preferred colors of red and yellow are used.

The horse’s mane has been highlighted in the preferred color yellow to help to answer the question below of how a horse and a deer are alike and how they’re different. The horse's ears and nostril are outlined in red.

Movement

Movement can be used to elicit and sustain visual attention.

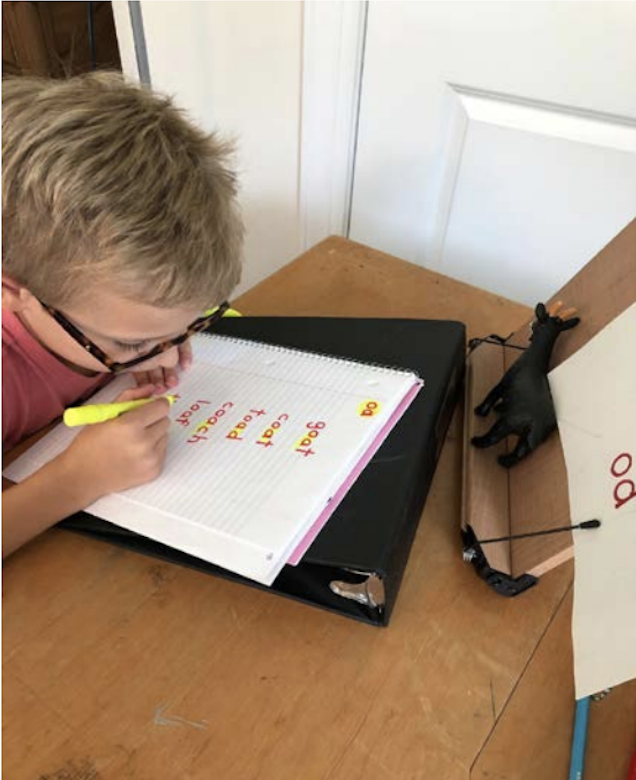

- Encourage student to use his or her finger under the text when reading.

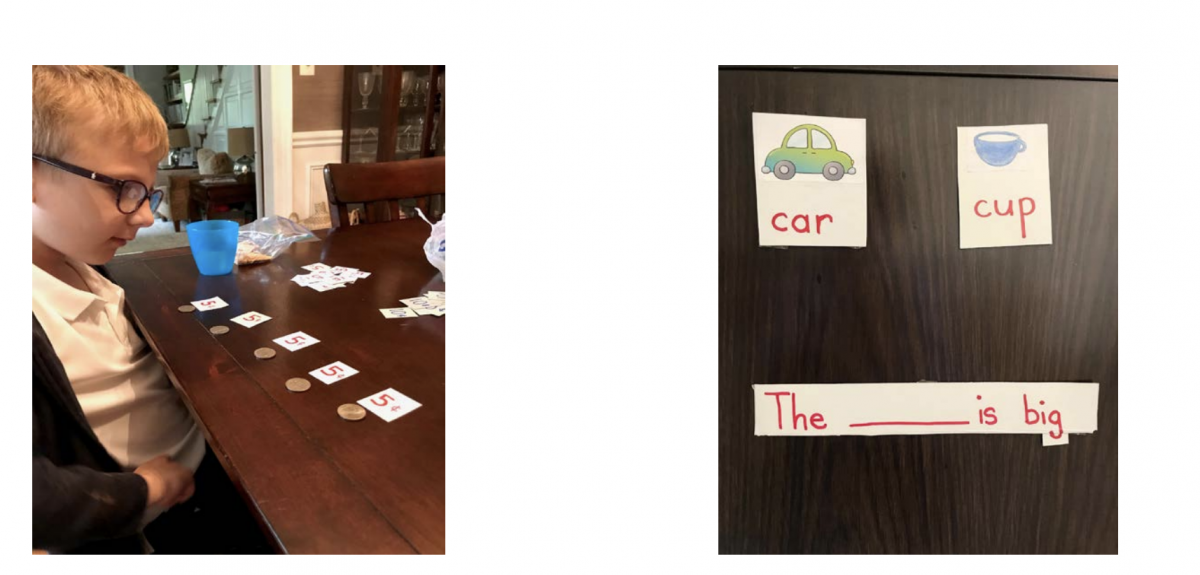

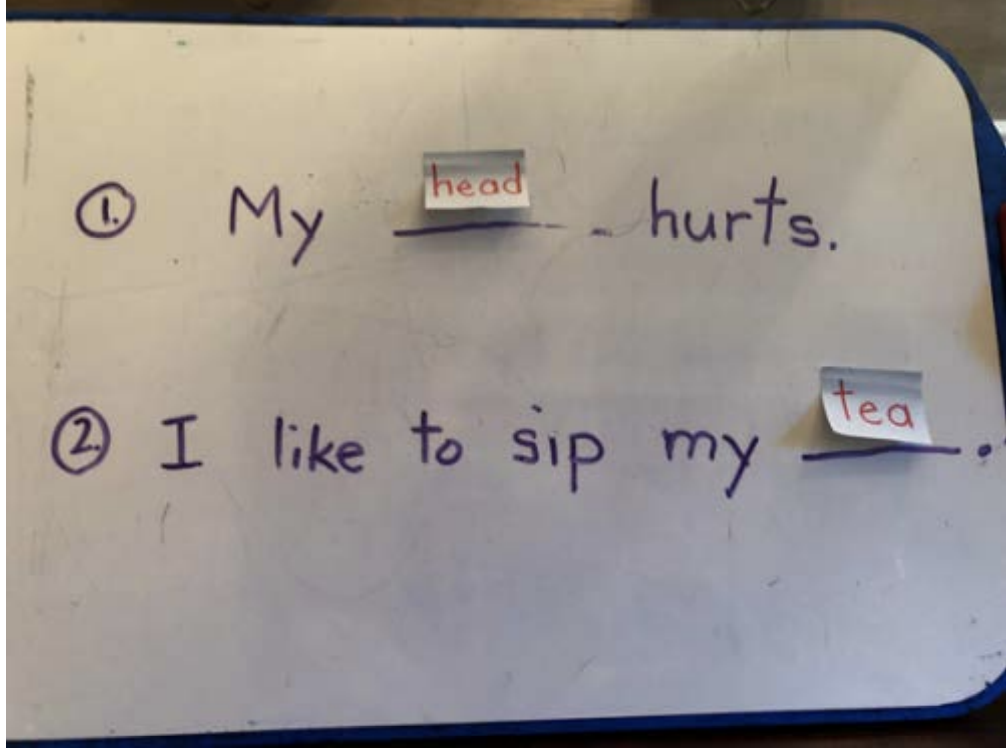

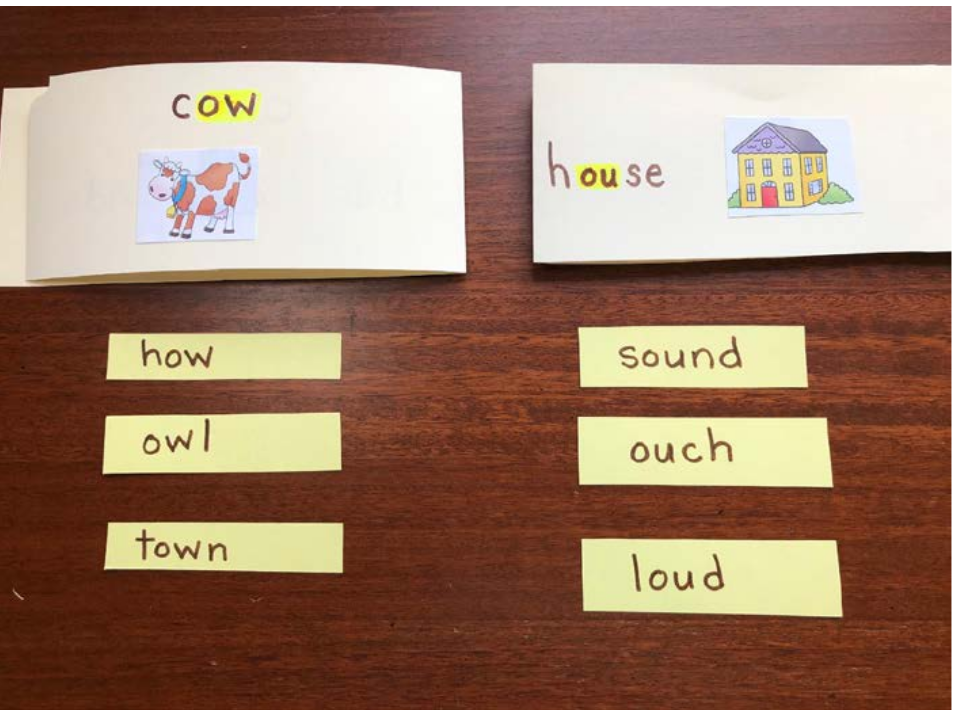

- Tasks that involve moving or manipulating items, such as letters, word cards or math items can be helpful.

- Find ways to respond to student’s interests, skills, and needs on the spot.

- Save student’s visual battery (or energy) for the central learning objective of the lesson, such as the two sounds of /ea/.

- Use videos to elicit attention.

- With targets at a distance, use movement to draw attention.

- Movement can be used to help extend the child’s visual battery.

- In school, movement is used as a break so that he is able to get out of his seat and then return to the task.

- Use of a pocket item to fidget with may help child to maintain concentration.

- Be sure to establish ahead of time what movement in which setting is acceptable.

- Movement in the environment may also be a distraction. Position the student so that his or her back is to the movement or create an “office space” that limits visual distractions.

Visual Latency

- Be aware of the demands of any given task. Delayed response looking at target is closely connected to difficulty of task, complexity of task, complexity of environment, and visual battery.

- Advocate use of “eyes off” label to mean a visual break while remaining seated

- Model self-advocacy statements, such as “I need a break.” This will help the student to learn to advocate for his or her own needs.

- Work to establish a CVI schedule for the school day.

- Observe visual responses to note visual fatigue and make adjustments

- Try to balance visual demands of task and environment. (Matt Tietjen has some helpful resources on this, in written format, as well as an online class. )

- Adjust pacing and duration of lesson.

Visual Field Preferences

Visual field preferences can change in novel environments. The lower visual field may be an issue.

- Adjust materials, both in terms of design and placement, to suit the learner’s visual field preferences.

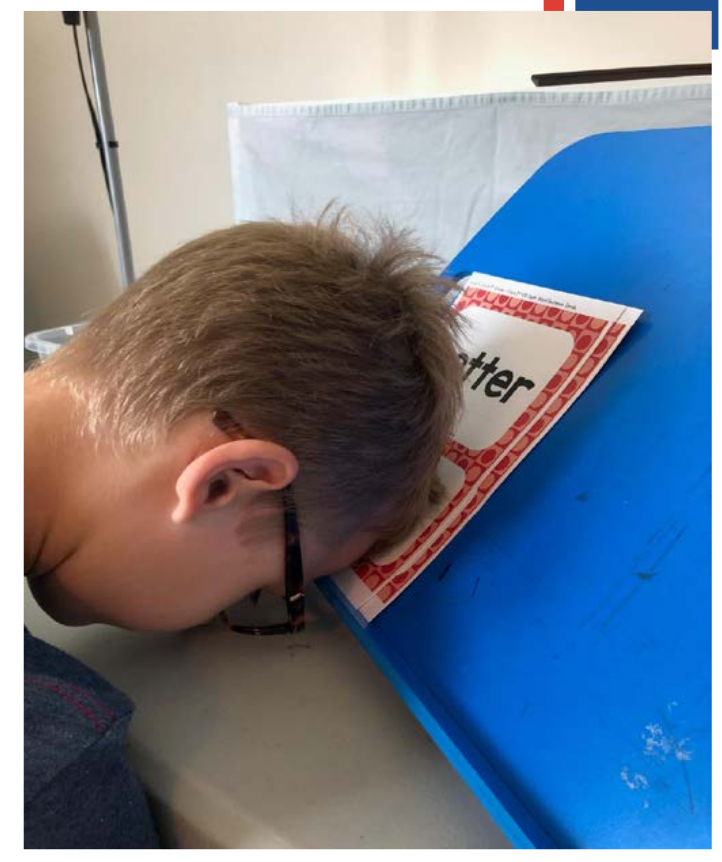

- Use a slant board for reading materials.

- Teach student to be his or her own advocate to determine what they need to do with the placement of materials, so that they are in the preferred visual field.

Visual Complexity

There are many parts to visual complexity. Learn more through Matt Tiejen’s work.

Complexity of patterns on the surface of objects

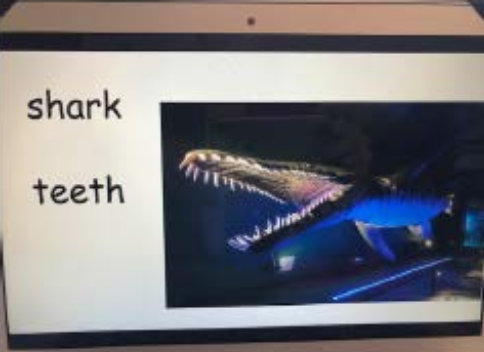

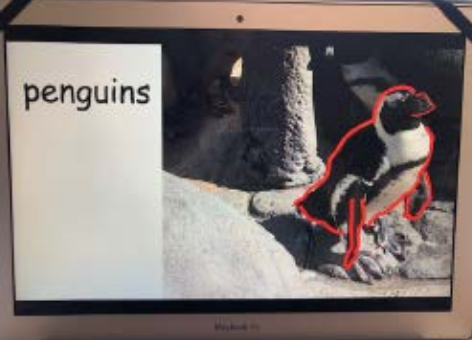

- Directly teach salient features of object, that is “two to three key visual features that are always or nearly always true of the object” (Roman-Lantzy, 2018)

- Consider the complexity of the surface of the object when images are used instructionally. It’s important to remember that, even if the child is looking at an image, that doesn’t mean that he or she is able to interpret it.

With this image of the sleigh from “How the Grinch Stole Christmas”, for example, the child may be familiar with the story and familiar with the concept of “sleigh”, but still be unable to visually recognize a sleigh by itself. When the image includes the bag of toys on top, that context may help the child to be able to identify it.

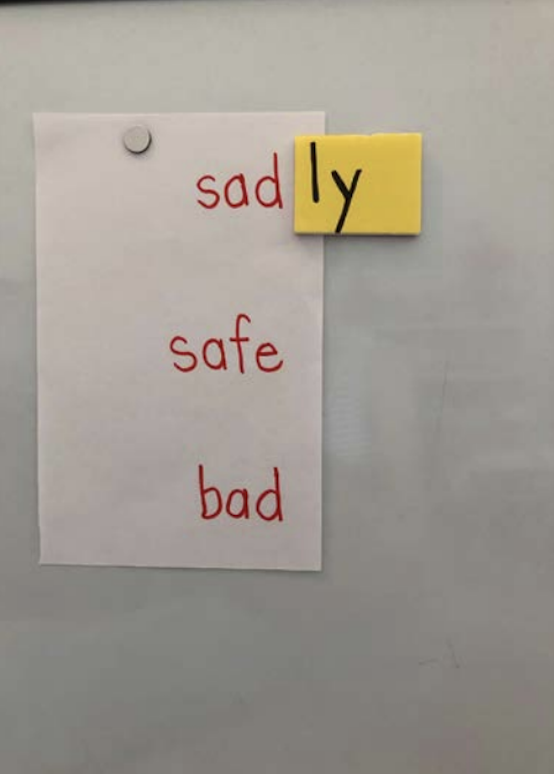

Complexity of symbols

- Literacy and mathematical symbols can present their own level of complexity.

- Consult the child about preferences for size and spacing of symbols.

- Separating text and pictures on Google Slides may be helpful.

Complexity of Visual Array

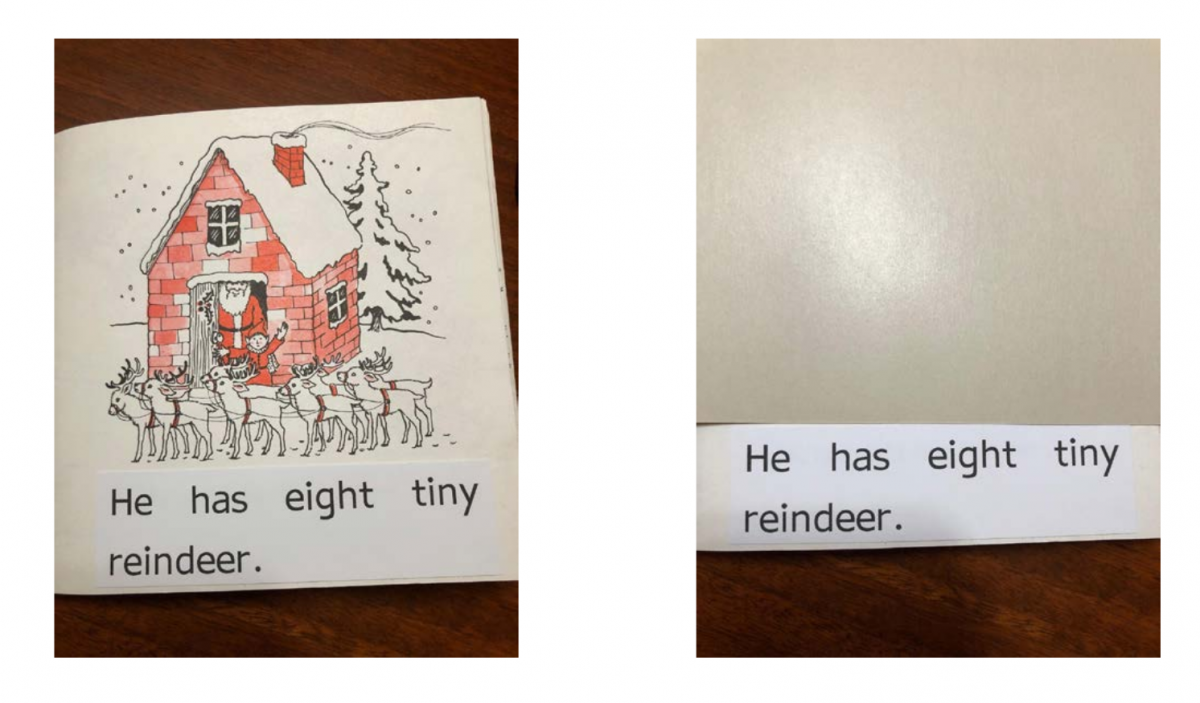

Students in Phase III often have difficulty disembedding a target from the background. Taking photos with an iPhone or iPad and removing the background, which makes the visual array very complex can be helpful. For things in the distance, taking photos can also be helpful. We often make books using these images and adding text. on Google Slides.

-

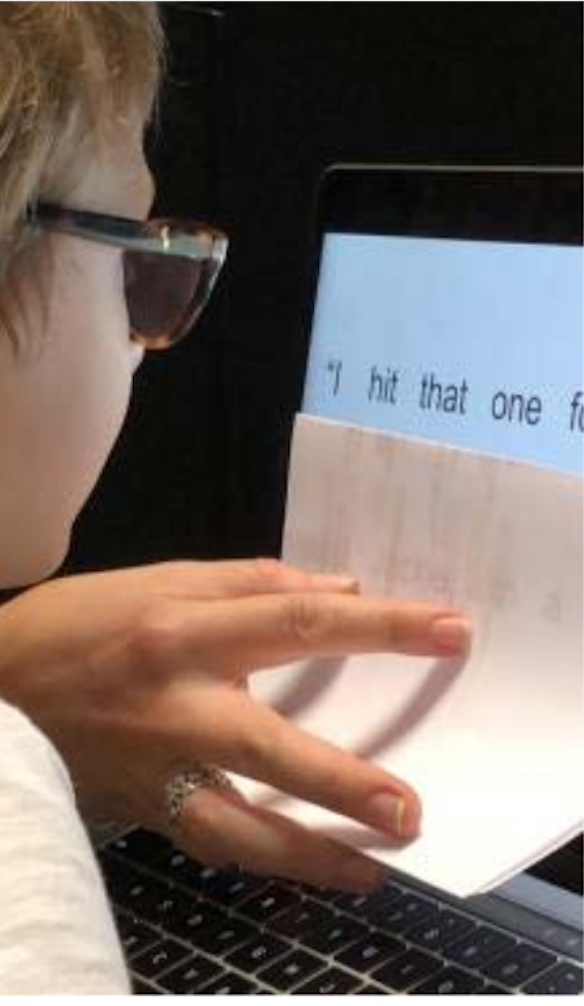

Physically reduce array in connected text.

- This can be done by rewriting the text, so that the student can access it visually.

- A blocker can also be used to cover the image, while trying to focus on the text only.

- Mask the extra information or mask the extra text.

- Use line markers, windows, or quadrant blockers.

- Make these blockers (which can be as simple as a plain piece of paper or oak tag) available to the student to advocate, select, use to help himself.

- Teach strategy of visual search following the same path as the hands of the clock.

- Organize work space and materials to reduce visual array and to increase predictability.

- Adjust array with sorting activities.

Complexity of the Sensory Environment

The sensory environment can draw attention away from using vision.

- Structure the environment as much as possible to support visual focus.

- Wearing headphones can help to limit sensory interference and promote concentration on an activity.

- Avoid talking to the student when he or she is doing a difficult task.

- Tap on the visual task to prompt the student to return visual attention.

- Share information with the student afterwards by comments, such as, "I noticed that when you ...". This can help the child learn to monitor their own behavior.

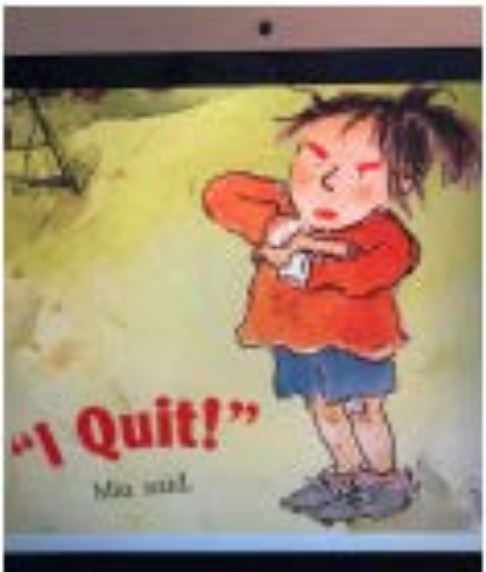

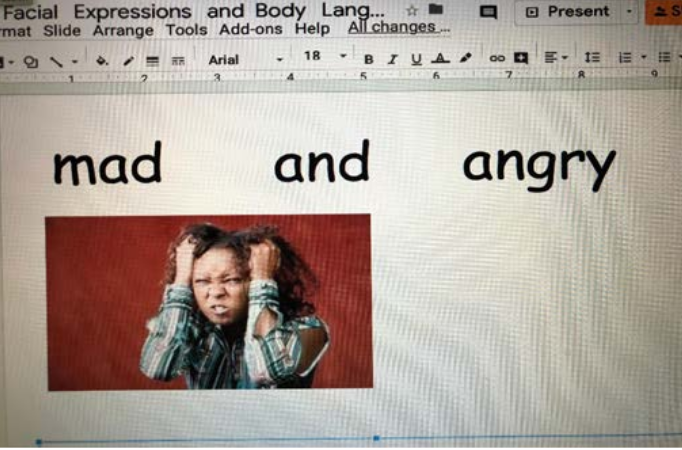

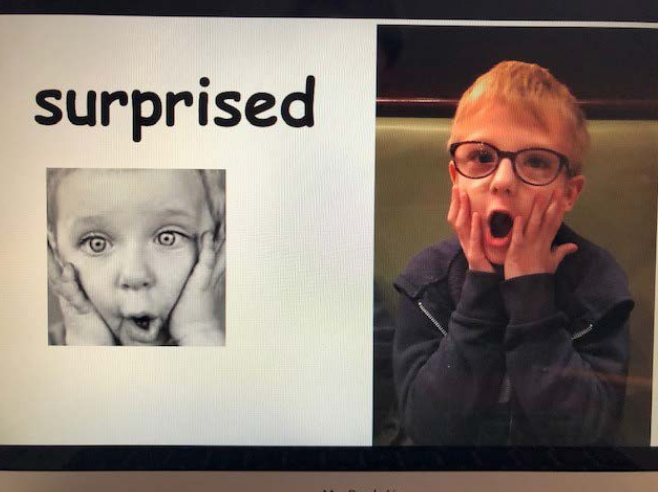

Complexity of Human Faces

The complexity of human faces are especially difficult in person, and can be even more so in a photograph. Discerning facial expressions of characters in story illustrations can be especially difficult for people with CVI.

- Provide repeated opportunities to look at and study a range of facial features.

- Discuss how body language connects with facial expressions and emotions.

- Model different expressions for the student and encourage them to demonstrate various facial expressions and body language.

Light

- Be aware of the challenge that glare may pose.

- Encourage students to advocate for themselves when they need more light.

- Backlight materials using an iPad to reduce visual fatigue. This can be especially helpful when reading instructional passages and new word skills.

Distance Viewing

- Present all tasks within child's “learning distance” (as noted in the CVI Range assessment), so that they are visually accessible.

- Use an iPad to photograph images at a distance and teach students to use the zoom feature to view images up close.

Visual Novelty

Students in Phase III become much more aware of novel objects in the environment.

- Use the salient features to learn about these novel objects and to learn new information.

- Expand the vocabulary that connects with it.

- Discuss salient features when teaching novel information and exploring novel objects.

- Present various examples, so that the student can learn to generalize salient features from the familiar to the novel.

- Use word cards to adjust visual array and adapt the activity to meet the needs of the student.

- Pre-teach vocabulary and concepts in novel texts.

- Introduce the child to novel newspaper and magazine images and words.

Resources

Fisher, K., and M. Immordino-Yang,(foreword). (2008) The Jossey-Bass Reader on the Brain and Learning. San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Lueck, Amanda H., and Gordon N. Dutton, editors. (2015) Vision and the Brain: Understanding Cerebral Visual Impairment in Children. New York: AFB Press.

Pinnell, G.S, and Fountas, I (1998). Word Matters: Teaching Phonics and Spelling in the Reading/Writing Classroom. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Pinnell, G.S, and Fountas, I (1996). Guided Reading. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Roman-Lantzy, Christine. (2018) Cortical Visual Impairment: An Approach to Assessment and Intervention. 2nd Edition. New York: AFB Press.

Roman-Lantzy, Christine.(2019), Cortical Visual Impairment:Advanced Principles. New York: AFB Press.

Shaywitz, Sally (2003). Overcoming Dyslexia; A New Science Based Program for Reading Problems at Any Level. NY: Alfred A. Knopf

Tietjen, Matthew. The ‘What’s the Complexity?’ Framework. Cortical Visual Impairment: Advanced Principles. New York: AFB Press.

Wylie, R.E., & Durrell, D.D. (1970). Teaching vowels through phonograms. Elementary English, 47, 787-791.

Websites

- CVI Scotland

- Innovative Resources for Instructional Success Center (IRIS)

- National Center for Education, Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE)

- Paths to Literacy

- Pediatric Cortical Visual Impairment Society

- Perkins CVI Hub

- ReadWorks.org

- Sage Journals, The Review of Educational Research (RER)

- Strategy to See

- Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired

- TextProject

- U.S. Department of Education What Works Clearinghouse

- West Virginia Department of Education - CVI Special Topics

Blogs and Social Media