Marnee Loftin is a psychologist, who recently retired from Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired. She is the author of

Making Evaluations Meaningful and has presented widely about learning disabilities in students with visual impairments.

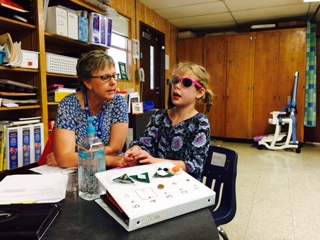

Missy is a bright and alert second grader. She began learning braille in her pre-Kindergarten class. Her initial progress was rapid, and Missy learned all of the letters within the first few weeks of school. Her parents report that she was “reading” her Dr. Seuss books each night, but that Missy seemed to struggle with recognizing the words when they appeared in other books. Missy began experiencing significant problems when the patterns of consonant-vowel-consonant words began to change. For example, Missy could read “cat” but struggled with “hat.” When asked to rhyme words, Missy would provide another word that seemed to have no relationship. The TVI initially told the parents that these skills would likely develop with maturity. However, by the end of first grade, Missy was still struggling. The TVI requested assessment with the reading intervention specialist, but was told that testing could not occur because the visual impairment could not be “ruled out” as the cause. Additionally the reading specialist did not feel that she could provide services to Missy without being a certified teacher in visual impairment. Intervention could only be provided by the TVI and parent. As second grade began, Missy began to develop behavior problems, often becoming uncooperative when asked to read by any adult.

Juan is finishing up third grade. He did extremely well in the first grade and was always proud of his academic skills. By the end of first grade he was able to read 100% of the first grade sight words. He was always eager to read aloud in class, and was eager to answer questions that were posed by the teacher. By the third grade, Juan has begun to struggle. He continues to sound out most words that he encounters and has become extremely slow with his reading. At the beginning of third grade his teacher timed his ability to read. She found that Juan was taking approximately 90 seconds to sound out words that he did not immediately recognize. Juan is so slow with his reading that he forgets what he has read earlier. Juan is becoming very resistant to reading aloud in class because other students are so frustrated with his slow speed. The TVI has done multiple analyses to determine if he is using the appropriate medium and remains adamant that it is not a problem with his vision that is slowing his reading so significantly. Juan’s mother found him crying in his room because he was so upset that the other boys on the bus were calling him “stupid.”

Gael is a braille learner who reads fluently at his current grade level of 9th grade. Gael is able to recognize almost 100% of commonly-used sight words. He reads with great expression while observing signs of punctuation and paragraphs. However, Gael understands very little of what he actually reads. When asked to answer factual questions, Gael can answer approximately 25% at the 9th grade level. He is not able to answer any questions that deal with inferences or reasoning. Gael is not able to retell the passage even when given an outline to structure his retelling. In measuring comprehension of materials, Gael is most successful when asked to respond to materials at the 3rd grade level.

Each of these children is unique with their history as well as their current performance. However each of them shares the characteristics of a specific learning disability in the area of reading. The way in which each of these children manifests their difficulties is different, but each requires some additional support from specialists in the area of reading.

Unfortunately this is a story too frequently heard about children who seem to start off as bright and interested readers. Somewhere along the way, the pattern changes and progress becomes slow or non-existent. A critical piece of an educational program is providing assistance to children who are struggling. Sadly, it is often a difficult task to broaden the team of individuals who work with students with visual impairments.

Intervention is most effective when it occurs early rather than late. However, many schools are hesitant to provide formal intervention for students with visual impairments. Some of the reasons for this hesitancy are:

-

Misunderstanding the nature of the visual impairment

-

Lack of clarity about the role of the Teacher of the Visually Impaired (TVI)

-

Fear that strategies for reading improvement will not be effective for the student with a visual impairment

For these reasons, the initial intervention may occur somewhat later for students with visual impairments. The TVI with the support of the parent will provide the initial intervention for a student who is struggling with reading. It is important that clear communication continues between parent and TVI and that the following issues be considered:

1. Problems are problems. How can difficulties with reading be considered as being different types of problems?

There are many differences in reading problems. They differ in how early they are shown as well as how basic they are to the whole process of reading. For example, like Missy, some problems show up early. Children may have good memories and be able to repeat simple books that parents have read often to them. However, eventually they are required to read the same words in different situations. At this point the problems become apparent. Again, like Missy, the child cannot read the word “hat” or “cat” when it appears in any book other than “Cat in the Hat.” These problems will be noted early, but are frequently not formally identified until beginning second grade.

As with many children, Juan seems to have mastered the initial stages of reading. They learn to sound out words, but never seem to move beyond to recognizing words immediately. Most readers past the second grade only sound out words that are unfamiliar. Other words are automatic and read naturally without even thinking about the process. For some children, reading never becomes an automatic process. Each word becomes a mystery to be solved. Typically these problems will become apparent during the third grade. By this time, reading has become an automatic process for most fluent readers. However, children such as Juan remain insistent upon the laborious process of sounding out each word. Rates slow and comprehension lowers as a result.

Gael represents another type of problem with reading. Many children can read well and have a large vocabulary of sight words. However, they have problems with understanding what they read. Sometimes these children can understand basic facts of a passage they have read, but miss the overall meaning. Children may also have difficulty in understanding inference questions, i.e. questions that have no clear answer in the passage. It may be difficult to understand that these children have reading problems because they are often such fluent readers. Their problems are equally significant and need intervention. Most often these problems will be noted by the fifth grade when children are asked to read more materials and to engage in more “thinking” and problem solving activities.

2. Does the type of problem make any difference in providing intervention? Wouldn’t more time spent on reading help with any type of problem?

As with any problem, solving a problem requires carefully considering what exactly is going wrong with the current situation. There are many different strategies that can be used to address the particular problem. Some of the possible strategies are listed in the section below.

3. With premature infants, many cautions are given about slowed developmental maturity. Is it possible that the problems in reading are simply the result of this slow down?

It is possible that children with ROP will have some initial delays in reading, and learning braille certainly presents some additional challenges. It is always frustrating for parents because they don’t have a clear guidepost for how reading should progress for a child with a visual impairment. The TVI will likely be the best resource to determine if reading progress seems exceptionally delayed. The critical factor is to provide intervention in a timely manner. Waiting too long for a child to mature is often a loss of valuable time for intervention.

3. Are some problems more severe than others? Will the problems disappear as appropriate intervention is provided?

The problems that appear earlier (difficulty in differentiating sounds and reading simple words) tend to be predictors of more severe problems. Even these are not full-proof predictors. Some children will eventually become fluent readers with little need for support. Some children will respond well to early intervention, but will need continued support. For another group of students with early problems, reading may remain difficult or sometimes impossible in spite of intervention and support.

4. If appropriate intervention is provided, shouldn’t all children learn to read? If my child is not reading, instruction must be incorrect.

For a number of reasons, some small percentage of the general population is not able to master the process of reading. A small percentage of the population with visual impairment will also have this difficulty. This is often the result of cognitive ability or specific brain trauma, but there is another group in which the causes remain unknown. No one is able to determine the exact reason for this difficulty. If this occurs, technology and creative minds have come up with many different ways to deal with this issue.

5. The teacher keeps asking us to practice the same sight words over and over. I know that my child is getting so bored by this process. Why is there such an emphasis on sight words when his phonics skills seem to be well developed? Why should he be memorizing words instead?

Many sight words don’t follow the typical rules of phonics. It is estimated that 100 common sight words make up at least 50% of all of the words read by adults. If your child learns these words fluently, he will be able to read a great deal of the material presented. He will also be a faster reader since he is not struggling with “sounding out” words that may not fit the rules. Help find a way to make these drills more fun. Perhaps a timed practice with the aim of beating the previous time or graphs charting progress might add a little excitement to the drills. Be sure that you are not communicating that it is a boring task!

6. We have finally moved past the boring sight word drills. Now the TVI is asking us to read books that I know are too easy for my child. Why can’t the TVI send home books for practice that present some challenges for her?

It is important that your child continue to practice books that allow her to read easily and fluently. The emphasis during home reading should be on reading smoothly without assistance from the parent. It allows your child to practice reading more rapidly and with more emotion. All of these are critical not only to building skills, but also building positive feelings about reading.

There are many books that deal with specific strategies that parents and teachers can use to help their child learn new skills in reading. Additionally, many examples of successful techniques are available on websites such as YouTube. The following are only a very limited number of some of the strategies available.

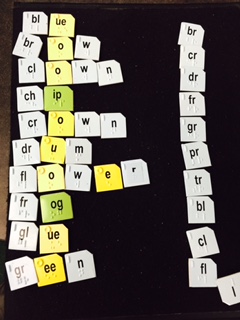

Problems in hearing the different sounds of words and syllables:

-

Recognizing rhymes (Which word does NOT belong: cat tree hat?)

-

Producing rhymes (How many words can you tell me that rhyme with “cat”?)

-

Matching sounds (Which word starts with different sounds: baby, ball, dog?)

-

Teaching segmentation (Break compound words into separate words.)

-

Breaking words into syllables (Count number of times chin drops.)

Problems with recognition of common sight words:

-

Increasing sight word vocabulary (timed drills using common words)

-

Differentiating similar sight words (eliminating different words from a page)

-

Drill, drill, drill (use techniques such as graphing times, racing against the clock to improve interest)

Problems with fluency:

-

Choral reading (Multiple people read together with emphasis on observing punctuation and emotions of the passage.)

-

Developing appropriate pace (Reading along with taped texts)

-

Using context clues (Encourage use of information in previous sentences to make an educated guess about an unknown word.)

-

Evaluating your guess at an unknown word (Read the sentence critically to determine any clues. Restating passages using your own words if it makes sense.)

Problems with comprehension:

-

Restating information/stories using words of the reader

-

Predicting outcomes based upon the introductory sentence

-

Discussing different outcomes that might have occurred

The outcome of any strategy is to help with the problem identified. The ability to determine if any strategy is effective depends upon both the TVI and the parent constantly reviewing the improvement of specific areas of reading.

If significant improvement is not noted, it is important that the child be referred for additional evaluation by a person skilled in the area of specific learning disabilities. Based upon this evaluation more specific interventions will be recommended. In addition, the evaluator may determine that another condition exists that may contribute to these difficulties.

If further evaluation is to occur, it will be important that the TVI be able to provide the following information to the Team with a recommendation for further evaluation:

-

Specific impact of the visual impairment upon overall reading process

-

Specific interventions that have been implemented

-

Response to these interventions

-

Specific problems that are still being experienced and their relationship (or non-relationship) to the visual impairment

Providing such information to the Team will allow them to determine that visual impairment is not the PRIMARY cause of the reading problem. It will also provide important information about interventions that have already been attempted.

Marnee Loftin is a psychologist, who recently retired from Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired. She is the author of Making Evaluations Meaningful and has presented widely about learning disabilities in students with visual impairments.

Marnee Loftin is a psychologist, who recently retired from Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired. She is the author of Making Evaluations Meaningful and has presented widely about learning disabilities in students with visual impairments.

Comments

Tips for teaching students with VI and LD