Pathways Towards Reading Readiness for Braille

Sighted children develop and gain knowledge and experience through incidental learning. During their first few years of life they have exposure to a vast range of visual symbols that convey meaning. They observe children and adults looking atprint and gaining meaning from the words they read.

Sighted children develop and gain knowledge and experience through incidental learning. During their first few years of life they have exposure to a vast range of visual symbols that convey meaning. They observe children and adults looking atprint and gaining meaning from the words they read.

Symbols are all around us in the environment and children experience them in many forms every day of their lives. Using signs, symbols and sounds to convey meaning and record knowledge is the basis for developing literacy skills. At four or five years old when the sighted child starts the formal process of literacy, they have already learnt a great deal incidentally about the world around them to support their understanding of concepts. They start by understanding what objects are and move onto what they are called. They then learn about how they are represented on paper – the written word

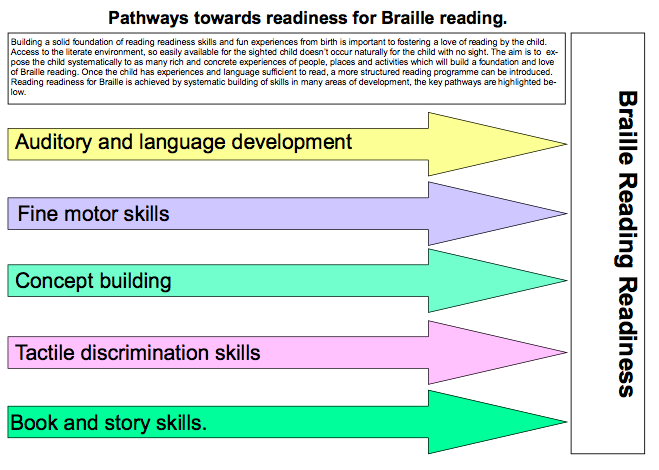

This access to the literate environment doesn’t occur naturally for the child with visual impairment. They need the same exposure to the written word as print readers, so that they can make the same connections and develop a concept of written language. Building a solid foundation of readiness skills and fun experiences from infancy is a critical part of the child’s reading readiness as well as fostering a love of books. Our ultimate goal is to expose the child systematically and as early as possible and often as possible to a rich variety of concrete experiences, involving many objects, people, places, and activities, which will support and build a foundation and enthusiasm for braille reading. Once the child has experiences and language sufficient to read, a more structured reading programme can be introduced.

-

Concept Building

Auditory Development

-

Sound – object/person + opportunity to explore object associated with the sound – (always reinforced with the spoken word)

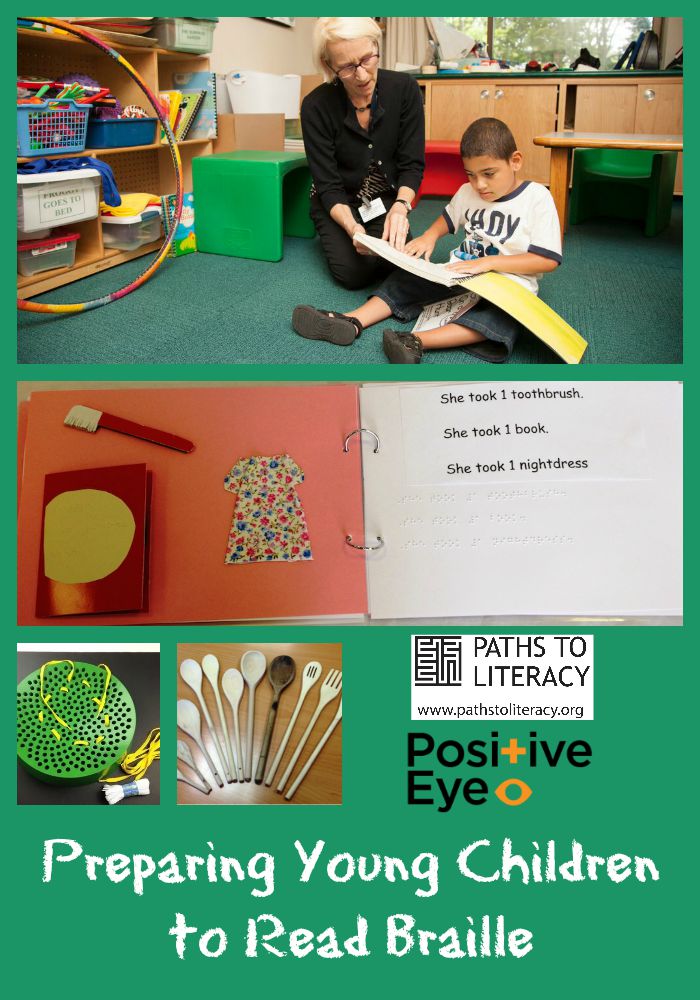

- Opportunities to create sound with a range of objects, pan lids, wooden spoons, musical instruments

- Action songs and rhymes, used with tactile representations of objects from the song or rhyme

- Introducing books with links to familiar songs, extending opportunities for using tactile representations

Development of Fine Motor Skills

- Wrist flexibility/finger dexterity

- Grasping skills

- Two handed coordination

- Hand and finger strength

- Finger position, finger isolation

- Light touch, tracking

Developmental Approach to Tactual Learning

- Awareness and attention of textures, temperatures and other characteristics of 3D objects of hand size down to smaller sized item. Discrimination of shape, size, weight, form

- Discrimination of smaller and smaller 2D representations of shapes using a variety of materials and textures

- Small objects and shapes positioned in rows on a page to representbBraille lines. The child learns to track along lines of string, ribbon, straws, recognising the odd one out

- Discriminate and recognise braille characters, identifying the odd one out, tracking along lines of braille patterns

Reading Awareness – Book and Story Skills

In order to develop positive attitudes towards reading, the child requires tactual readiness materials just as seeing children need visual reading readiness materials. They need additional experiences in handling and exploring books, with lots of opportunities to use tactile books as toys, with textures and sounds, real objects or representational objects to motivate them to explore and enjoy the story whilst being read to.

- Identify parts of the book, cover, pages, margins

- Hold and turn pages from left to right

- Understand simple reading directions given by the teacher e.g. top, bottom, left, right

- Find specific shapes located at different points on each page, as the child progresses through the book, each page becoming a little more complex with the addition of other shapes and textures

Braille Reading and Writing Mechanics:

- Reading surface should be of sufficient size to support the whole book and should be no higher than the elbow level of the reader. (A reading surface above elbow level causes the child to hunch their shoulders or to spread elbows apart, thus pulling hands into a poor reading position.)

- Both feet on floor, child’s back against back of chair

- Use both hands together on the braille line with the thumbs gently touching and the upper joints of the index fingers in light contact with each other.

- Wrists should neither be sagged nor be humped.

- Coordinated use of both hands is characteristic of efficient braille reading. While the right hand completes one line the left hand moves to the beginning of the next line to continue reading. The two hands then meet at some point approaching the middle of the new line, separating towards the end of the line to perform their separate functions. Two hands that function together efficiently create the most efficient readers. Quick smooth left–right hand movements are characteristic of efficient braille readers. For the sighted reader visual perception occurs as the eye pauses, for the braille reader tactual perception is achieved through movement across the symbols.

- Braille is perceived through the pressure points within the surface of the finger pads. Hands are positioned to make the most efficient use of the finger pads on the reading surface, to allow the pads to focus most of the attention on the upper part of the cell, where the majority of dots appear, but also to span the entire three dot depth of the cell. The tips of eight fingers or at least the first three on each hand should curve naturally and rest lightly on one line (the reading line) enabling them to slide quickly and easily from left to right. The child should lift fingers to return to the beginning of the line.

- A very light finger pressure is conducive to good perception. A heavier finger pressure spreads the perception points and blurs the image. The teacher may demonstrate light pressure by placing hands in the reading position and sliding along child’s arm. The teacher may ask the child to do the same along his/her arm to judge the child’s pressure. Perspiring and/or whitening fingers are indicative of too much pressure.

- As many fingers as possible should be utilized. Most children use the index finger or the index finger and middle finger on one or both hands as the primary reading fingers. Other fingers serve to maintain orientation on the braille line, to pick up the missed cues and correct faulty impressions, or to move ahead perceiving punctuation or checking to make sure the line is completed.

- When re-locating and moving to new reading line, the child should not be allowed to retrace the braille line from right to left. The re-tracing of the braille in reverse may lead to reversal problems.