Culturally Responsive Literacy Education with Learners Who Are Blind or Visually Impaired

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) is ubiquitous in mainstream education circles, yet it doesn’t receive much attention in the world of blindness/visual impairment (b/vi) education. This article discusses why CRP matters and how it can be infused into tactile/auditory/digital literacy learning with students who are blind or visually impaired.

Defining CRP

CRP was originally conceptualized over twenty years ago by Dr. Gloria Ladson Billings, who used the term Culturally Relevant Pedagogy to describe a way of teaching that promotes the academic success and critical consciousness of African American students by using cultural referents to impart knowledge.

Since that time, CRP has been expanded by several scholars through iterations such as culturally responsive, culturally congruent, and, most recently, culturally sustaining pedagogy. Drawing from this family of pedagogies, I will refer to CRP inclusively as any teaching that 1) empowers students by using their cultural characteristics, experiences, and perspectives as conduits for learning, and 2) sustains and extends the rich languages, literacies, and cultural practices of all students, particularly those who disproportionately experience educational underachievement.

The Case for CRP

There are three primary reasons why CRP matters for blind/visually impaired (b/vi) students. First, and perhaps foremost, is the salience of culture in our lives. We all have culture, whether we are aware of it or not. The cultures that we carry are deeper than surface manifestations, such as food, clothing, and music. Culture is also reflected in how we think, believe, and behave. It shapes how we teach and learn. It is at the heart of education.

CRP is also essential in contemporary education because of the shifting demographics of the U.S. and its schools. The new mainstream of America’s school-aged population is multilingual and multicultural. According to federal education data, students of color make up 51% of the nation’s public school students. Blind/visually impaired students are no exception to this demographic reality. Statistics indicate that the racial breakdown of the b/vi student population is similar to that of the larger student body.

Despite the dramatic shift in the cultural diversity of students, the standard curriculum, instruction, customs and teacher force of America’s schools continue to reflect the dominant, European, middle class culture. CRP broadens the center of teaching and learning and affirms the plurality of cultural beliefs, practices, and ways of being that the diverse student body brings to the classroom. This approach has been found to boost self-confidence, engagement in school, and academic success among Latinx, African/African American, and Indigenous/First Nation students, who have traditionally underperformed academically.

The benefits of CRP can also extend to students with visual impairments. Though more research is needed, there are already some data indicating racialized reading disparities among b/vi learners. A national study of more than 11,000 special education students found that Black and Latinx students with sensory impairments had considerably lower oral reading fluency rates than their White peers.

CRP can be an effective tool for improving literacy outcomes for racially and linguistically diverse b/vi students. However, it is important to recognize that CRP is not just for some students. CRP is an approach to teaching and learning that has benefits for all students. In our global society, all students need to be prepared to access opportunities and power, which will increasingly become more reflective of diverse cultures and languages.

CRP Principles and Practices

A disclaimer is in order at this point. It is important to recognize that CRP is not a one-size-fit-all method or a quick fix. CRP is a context-driven approach which recognizes that culture is fluid and that cultural differences exist within ethnic groups based on social class, age, and where people live in the country.

Regardless of the varieties of cultures and languages that are present in a given learning environment, there are several key ways that educators can infuse CRP into their work with students. Below, I share five CRP principles and practices that TVIs and other educators can use in their literacy instruction with b/vi students.

1. Get in touch with your own cultural identity.

In order to better understand and respond to students from different cultural backgrounds, it is important for you to first identify your own cultural frames of reference. You may have ideas about what is and isn’t respectful, or a parent’s role in their child’s education, that are very different from what your students learned in their family. These kinds of cultural mismatches can cause you to misinterpret student behaviors.

When you become acquainted with your own cultural ideas and beliefs, you can widen your interpretation of students’ behaviors and more effectively respond to them. CRP scholar, Zaretta Hammond, provides a useful self-inquiry tool for identifying your cultural frame of reference in her book, Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain.

2. Build your cross-cultural knowledge.

Taking the time to learn about your students’ cultures is an important part of practicing CRP. This involves an ongoing process of self-education that you can engage in by doing the following:

- Listen to/read books and novels by authors of color.

- Attend a neighborhood event or institution, such as a church or mosque. When in these spaces, observe people’s communication styles and social norms, without judgment. This can give you valuable insight into your students’ community and family cultural practices.

- Watch positive movies and documentaries that present different cultural experiences. Netflix has some good ones for this purpose. Another great resource is Kanopy.com, a free online video streaming service that features documentaries and independent films, many of which have cultural and social value. Kanopy is accessible with a library card.

- Enlist parents as cultural brokers, meaning providers of knowledge about their heritage and family practices. A very helpful way of doing this is to survey parental perspectives, ideas, and interests. For example, here is an excerpt of a completed parent survey. The parents' responses provided helpful information fthat I was able to incorporate into my lesson planning.

3. Affirm students’ languages.

Language is a central part of culture, and sustaining diverse cultures in the classroom requires an understanding and appreciation of diverse language practices. Culturally and linguistically diverse students often use different language varieties, such as African American English (AAE), or a mix of two languages, as in Spanglish or Chinglish. These languages are typically looked upon negatively because they are not “standard” English. From a linguistic standpoint, however, all languages have their own set of rules and usage patterns. Therefore, no language variety is inherently superior to another.

Culturally responsive educators value their students’ different languages, rather than treating them as deficits to be limited or overcome in the learning process. This approach empowers students by helping them feel comfortable being their whole selves, which promotes increased interest and enhances their literacy learning.

A core CRE practice in writing instruction is to allow students to use the language with which they are most comfortable while also helping them develop proficiency in Dominant American English (DAE). This approach is highlighted in the activity described below with a high school students with multiple disabilities who is developing literacy skills.

This excerpt of a student’s response to a summer writing prompt demonstrates the use of AAE, including the infamous, English double negative (“I ain’t never”) and irregular verb forms (“A ride be just a ride”). When the student and I went over his story and the AAE word usage, I did not apply any negative connotations to his language. Instead, we talked about the meaning of his words, such as how the double negatives added emphasis to the dialogue. He told me that he liked saying the words that way, which I affirmed and accepted.

Next, I guided the student in writing a second version of the story using DAE. I explained to him that this was the language that he would have to use in certain academic/formal situations. I also emphasized that neither language variety is better than the other. We discussed how he will sometimes need to switch between his preferred AAE and DAE or use a combination of the two, depending on the context.

The student was also able to compare the braille contraction usage between the two language varieties, noting, for example, how the words goin’ and going had the same meaning but their different spellings required different contractions and punctuation. His second version of the story included both DAE and AAE. He was very proud of and pleased with both versions of his story, and he was excited and happy to know that he could develop his proficiency in DAE without having to discard his preferred English language variety.

4. Build a curriculum around student narratives.

Culturally responsive literacy instruction centers students’ lived experiences and cultural ways of being. One way to routinely do this with students who are learning braille is to replace monolingual and monocultural contraction practice sentences and reading passages with student-generated narratives. This approach not only helps learning come alive, but it also sends the message to students that their diverse cultures, languages, and literacies are an important and valued part of their education.

This is an example of a student’s story about the Indian food that she typically eats. She is the only Indian girl in her small class of students with multiple disabilities. Through her narrative, the student was able to share information about the food that she eats with her classmates. With input from her mom, I worked with the student on developing her story and including descriptions of the different food items. A list of culturally responsive vocabulary words were also generated from the story, which was a great extension of her narrative-writing process.

Student narratives do not have to be about a cultural topic in order to be considered culturally responsive. What matters is that the student voices and experiences are centered. In this short narrative that was written as a part of a braille contraction review, a student describes a weekend shopping ritual with his parents. This is a culturally responsive story because it represents characteristics of his close-knit, Portugese family.

In another instance, a student developed a set of sentences that described different summer activities in her neighborhood. The only requirement being was to incorporate at least one of her newly learned braille contraction word in each sentence. This is an engaging and authentic writing exercise that helped to solidify the student’s learning of braille contractions.

Student narratives like those described above are highly effective CRP tools because they tap into the oral and communal traditions that linguistically and culturally diverse students bring to the classroom. In addition to storytelling, students should be immersed in word play, talk/dialogue, memory games, rhymes, and riddles. These are all tools for learning that reflect traditional practices of African American, Latinx, Asian/Pacific Islander, Arab, and Indigenous/First nation cultures.

5. Read and teach from culturally diverse texts.

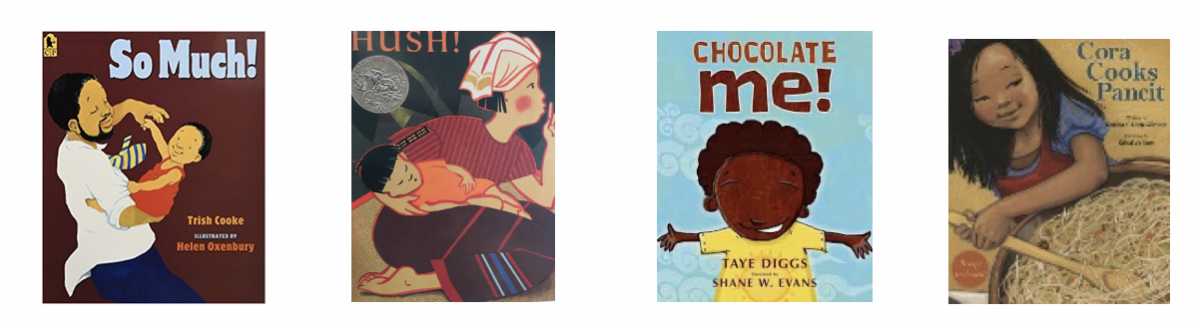

It is widely recognized among children’s literature scholars that young people's self-concept and literacy learning is enriched by books that reflect their worlds and that introduce them to different worlds and experiences. Though this post is focused on cultural diversity, characteristics such as ability, race, class, and gender are also important types of diversity that children should be exposed to in the books that they read.

Culturally diverse books bolster the self-esteem of children of color by providing them with positive images about their racial and ethnic identities. Culturally diverse books can also serve as an effective tool for improving reading engagement among learners from non-majority backgrounds. Furthermore, all students can benefit from books that allow them to learn about and come to value different cultures.

Despite the known benefits of exposing children to diverse texts, there has been a longstanding underrepresentation of non-White cultures in the world of children’s books.The lack of cultural diversity in children’s books is a widely recognized issue that dates back decades. This problem is also evident among published children’s braille books. In a recent analysis of more than 600 titles from the catalogs of several major children’s braille book publishers, I found that non-White cultures were represented in a mere 15% of the books.

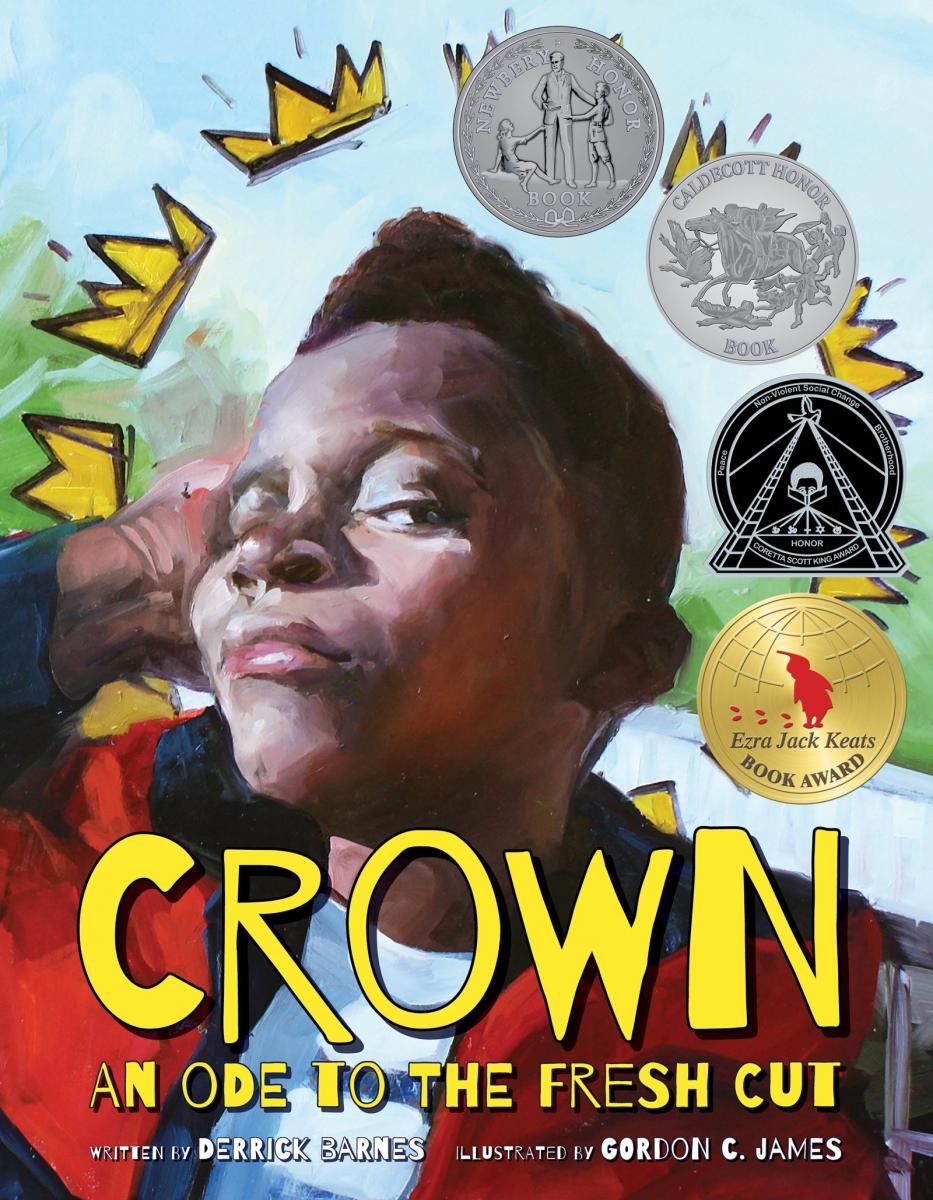

This diversity deficit means that teachers have to reach beyond the catalogs of published children’s braille books to access a range of books that feature culturally conscious content and themes for their students. Here is a list of books that would make a wonderful addition to any child’s early literacy experience. Some of them, like the one shown below, make really good story boxes!

Storybox items include cape, medal, blush brush, and modeling clay, as pictured below.

CRP Resources

To learn more about CRP, check out the following resources which I have found helpful in my research and practice.

- Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice by Geneva Gay

- Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain, Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students by Zaretta L. Hammond

- Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies by Django Paris and H. Samy Alim

- Yes, But How Do We Do It? Practicing Culturally Relevant Pedagogy by Gloria Ladson-Billings

Listen to the Sense of Texas podcast with Monique Coleman on this topic.