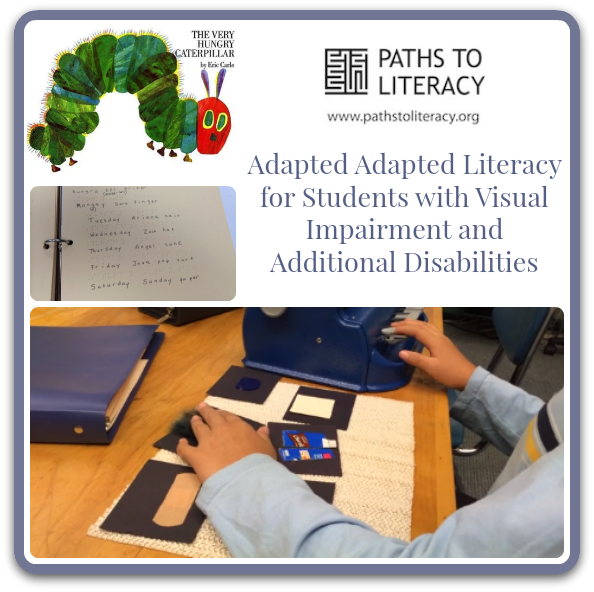

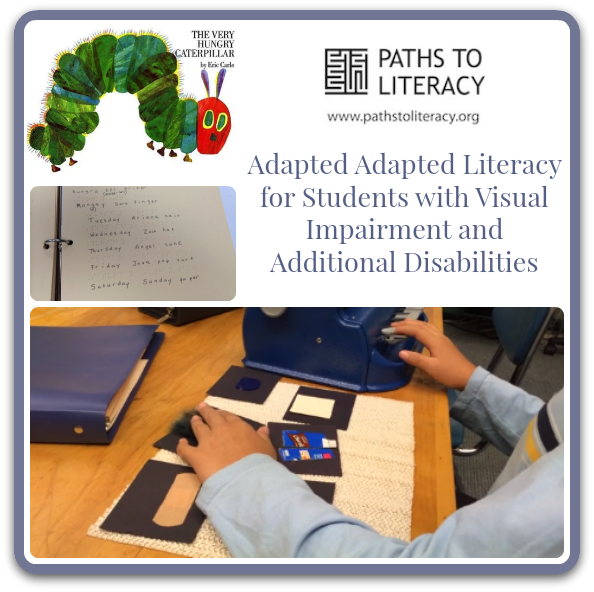

Buried deep in the Paths to Literacy archives is a little post called Adapted Adapted Literacy. It describes how my TVI colleague Sheryl Katzen and I worked together to adapt parts of our school’s conventional English Language Arts Curriculum for elementary students who functioned across a spectrum of early literacy and communication skills.

Why the “Adapted Adapted?”

Consider what you might imagine for an adapted board book version of The Very Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle. Perhaps it would look like a conventional print book with braille thermoform “stickies.” Maybe it would even have some tactile features that correspond with a hungry caterpillar or the food he is devouring.

Now consider a group of emerging readers and writers with limited background experiences who are still developing so many early concepts about the world because of their absent or distorted distance sense(s). Consider students who are also English Language Learners, some on the Autism Spectrum, and others with Intellectual and/or Physical Disabilities. When we used “adapted” literature materials, we found that some of our students could memorize parts of the story and stay minimally engaged. There was very little independence in our students’ interactions. Responses relied on prompts and a lot of direction from staff. Overall, most of our students did not comprehend the material and passively attended our group. Others rocked and poked their eyes – a sure sign that our learning media was not adequately adapted to meet their learning needs.

If my students’ hands and fingers are on adapted reading material, I want it to be of the highest quality and carry the most meaning. With comprehension comes engagement, enjoyment, participation, and active learning. These were our goals for literacy and communication for the students. Enter the extra ADAPTED!

If you’re having trouble imagining that extra ADAPTED, my student and I made a video to help you along. Enjoy the original work titled The Very Hungry Braillewriter.

You have the pleasure of seeing this author show off his finished product. As with any form of literacy and communication intervention, you know there is a process that precedes this piece of student-generated literature.

Sheryl and I took the concepts from stories, fables, and poems in the curriculum and re-wrote them with our students by using:

-

The students as the characters

-

Our immediate classroom environment as the setting (eventually we ventured into other familiar school settings such as the cafeteria or music class)

-

Recent experiences and daily routines as the plot

-

Quality Learning Media to represent vocabulary and concepts from students’ own experiences. There were 3 requirements for the media:

-

Meaningful (our student doesn’t just memorize it, they know what it represents)

-

Hands-on (something our students can touch, manipulate, and move)

-

Permanent (a spoken word is gone once it’s said, a tactile or picture symbol stays put!)

Where did we get a Very Hungry Braillewriter?

I was working with a small group of emerging readers and writers in middle school when one of my student’s braillewriters jammed while she checked her work. She attempted to un-stick it when the embossing head came down on her finger. “Ouch!” she exclaimed loudly. After making sure she was okay, I jokingly followed with “Geez. That Braillewriter must be pretty hungry if it wants to eat your finger!” A different student started to giggle, and then the student next to him began to giggle. Then the student with the pinched finger started to giggle and replayed the incident about 3 more times followed by collective laughter. An Adapted Literacy topic fell into our laps yet again. We had 4 characters, we had a setting, and we had a very funny experience to write about. We took turns figuring out what the braillewriter would eat next. When we ran out of characters with a few more days left in the week, we even learned to improvise. Now we just needed some learning media to document our thoughts in permanent form.

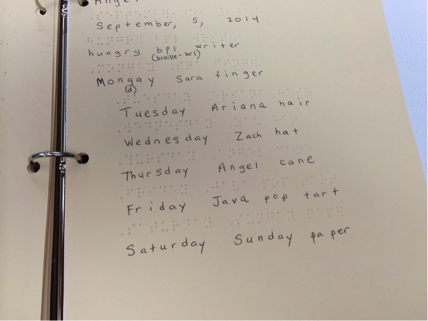

One of my early braille readers/writers helped me plan a story that would be titled “The Very Hungry Braillewriter” in a one-on-one session. He categorized the WHEN, the WHO, and the WHAT of our story using conventional braille media. This would help us plan the construction of our tactile media.

We decided to make one symbol that could represent four different concepts and/or vocabulary words (the when, the who, the what, and the exclamation):

For example, a band-aid tactile symbol represented the following 4 words:

-

Monday

-

Our classmate’s name

-

Her finger

-

Ouch!

It also represented the sentence, “On Monday, the hungry braillewriter ate Sara’s finger. “Ouch!”

Once we (the student and I) made 4 sets of tactile media, it was time to introduce it. I had to consider how much time my students needed to explore the tactile features of each symbol and just as importantly, how they needed to explore those features. One student scanned each texture one-by-one on her desk; another picked each up and took a very close look using her residual vision. One student needed to flap each of his symbols in air to study the weight of each card. This was a great opportunity for us to discuss the vocabulary for the story together and model the language that accompanied each symbol.

After exploring, it was time to put the events of our story in order and make sure we were all “on the same page.” A quick comprehension check is seen in the next video. The student’s left hand correctly identifies the characters in the story.

Have you ever asked your students with visual impairments and additional disabilities to “follow along” as you read? Have you done this with confidence they understood what you were reading AS they followed along? Check out our next video, using a combination of student-made tactile symbols and a motivating sound effect to reinforce listening, understanding, and engagement. Think about a student who is at the earliest levels of communication and literacy and putting him/her in charge of a sound effect using an AAC device or the actual object that makes the sound. This is often a very motivating job during read-aloud, and reinforces listening skills, turn-taking, and initiation.

You will remember the student’s independent reading of the story from the beginning of this post. There were a couple of moments when his retell got a little jumbled. This really pointed out a key feature to this process: If my students have access to understandable tactile forms of media they can make mistakes... and I can let them! Watch again with special attention to what the braillewriter ate on Wednesday and the days of the week for the last event. Look for the student's access to self-correction (no adult prompts!).

This process took about 3 weeks with two 30-minute sessions each week. We were able to continue our story extensions for another week and target a lot of different literacy and communication skills. We were also able to share our story with the Assistive Technology Specialist at our school, who was able to reinforce the students’ technology skills using a motivating, familiar topic.

Check out what happens when I really throw a wrench in the story re-tell. The student loses the sound effect because his two hands were too busy re-telling the story with a twist.

Comments

Meaningful tactiles

Spelling...